View basket (0 items $0.00)

Yoga, Osteoporosis & Vertebral Fracture Risk: Pros & Cons of Twisting Yoga Postures

Osteoporotic fractures become a significant health concern as people get older. In fact, the risk of incurring an osteoporotic fracture of the hip or wrist as well as vertebral fractures is on par with the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Many people with an osteoporotic fracture never fully recover; and in fact, for women with osteoporosis, the risk of dying from hip fracture is similar to the risk of dying from breast cancer, according to researchers.

Yoga for Osteoporosis: What Does the Research Say?

With the growing number of studies documenting yoga’s health benefits, there is increasing interest in whether yoga might help counteract the effects of osteoporosis. At the same time, this has also given rise to questions around the relative safety of different yoga postures for people with osteoporosis.

Encouragingly, several studies over the last ten years indicate that yoga offers benefits for people with osteoporosis. A small 2009 study found that a 12-week program of weight-bearing yoga with 3 weekly sessions slowed bone resorption, a marker of bone loss that has been linked to osteoporosis risk in women after menopause. The yoga program also was linked to overall better physical functioning and health, reduced pain, general health, and improved vitality, according to reports from study participants.

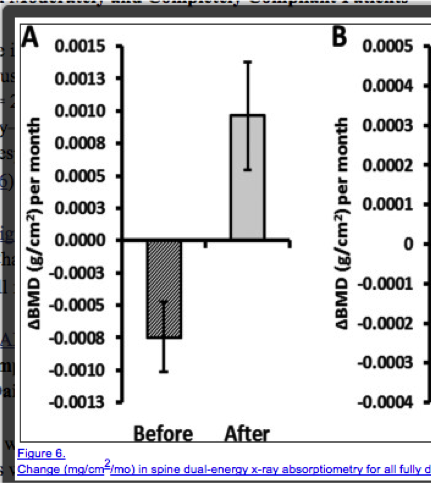

In addition, a 2016 study by Motorwala and colleagues followed a group of 30 women aged 45 to 62 with osteoporosis over a six-month period during which they participated in a one-hour yoga session four days a week.

At the end of the study period, participants showed increases in the bone mineral density of the spine, as indicated by improvement in DXA scan T-scores. Scores increased from a pre-study average of −2.69 to an average T-score of −2.55 post study. This is a 5.2% improvement, comparable with improvements seen in a review study showing the effects of long-term use of osteoporosis drugs like Denosumab and Alendronate.

One of the largest studies on the effects of yoga for osteoporosis was performed by Dr. Loren Fishman and colleagues. The study followed a group of 227 women who performed a 12-minute daily yoga program regularly over two years.

One of the largest studies on the effects of yoga for osteoporosis was performed by Dr. Loren Fishman and colleagues. The study followed a group of 227 women who performed a 12-minute daily yoga program regularly over two years.

The study found that bone mineral density improved significantly in the spine, hip, and femur. No yoga-related injuries were reported or observed on follow-up DXA scans.

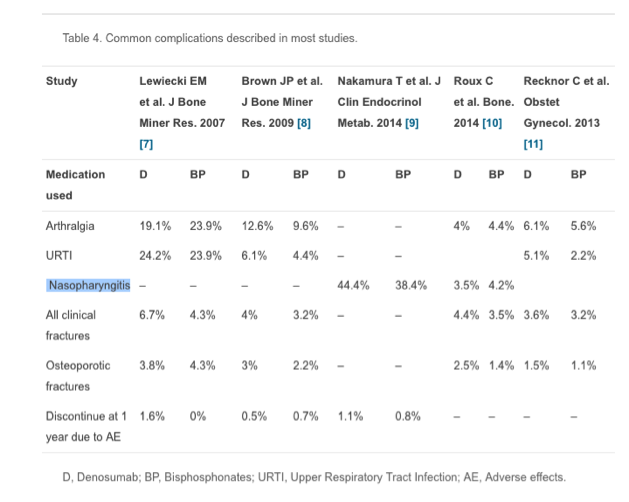

Notably, the studies looking at the effects of yoga for osteoporosis reported no adverse effects. In contrast, a review study of the effects of osteoporosis drugs reported surprisingly common side effects.

Side effects varied across studies, as noted in the table below (from the review article by Benjamin et al.), but 4% to 23.9% of participants reported joint pain (arthralgia); 2.2% to 24.2% experienced urinary tract infections, 3.5% to 44.4% experienced upper respiratory issues, and so on.

In contrast, yoga can be said to produce a number of side benefits for people with osteoporosis. Not only might it lead to improvements in bone mineral density, but yoga leads to overall improvements in physical fitness and ability to balance, factors that also significantly lower the risk of falls and fractures.

Which Yoga Poses Are Best for Osteoporosis? Which Should Be Avoided?

The studies on the benefits of yoga for osteoporosis are preliminary, and study results need to be confirmed by more robust, randomized controlled studies.

Still given the favorable results and the apparent lack of downsides from using yoga to help counteract osteoporosis as compared to osteoporosis drugs, this is an obvious area of interest for anyone with osteoporosis.

When looking at the benefits of yoga for osteoporosis, however, the question of safety also must be addressed. Do all yoga poses benefit people with osteoporosis? Or are there any poses that should be avoided?

This has proven to be an area of some controversy. Both Dr. Fishman’s study and the 2016-study by Motorwala quoted above used a wide range of postures, including twisting postures like Ardha Matsyendrasana, Marichyasana II, Trikonasana (Triangle pose), and Parsvakonasana (Extended Side Angle Pose). In the case of Motorwala’s study, a seated flexion posture was also included, i.e. Paschimottasana (Seated Forward Bend).

Flexion vs. Twisting Yoga Poses for People with Osteoporosis

The standard recommendation for movement to protect against vertebral fractures in people with osteoporosis, as e.g. put forward by the National Osteoporosis Foundation, is to avoid movement and yoga poses that involve flexion of the spine.

Some schools of thought also recommend against twisting movements of the spine, or advise caution, recommending to twist only “to the point of strain.” Hence, yoga postures involving these movements are also considered contraindicated.

Yet, in both Dr. Fishman’s study and the study by Motorwala et al., twisting yoga postures were included without any reports of adverse effects. What gives?

Vertebral compression fractures do occur without noticeable symptoms in many people, so one might argue that fragility fractures could have occurred without study participants realizing it.

Yet, not all vertebral fractures are silent, so in the case of Dr. Fishman’s study, which included 227 women, if fractures did occur, it is not likely that all would have been asymptomatic. Further, on follow-up DXA scans from 150 women in Dr. Fishman’s study, none of the DXA scans revealed any vertebral fractures, according to Dr. Fishman.

There is ample biomechanical foundation for the caution against flexion of the spine for people with osteoporosis. A 1984-study by Sinaki and colleagues also provided evidence for this risk; the study found higher incidence of vertebral compression fractures in a study group doing spinal flexion in a chair, plus sit-ups on the floor.

Biomechanically speaking, the anterior part of the vertebrae is the most vulnerable part of the vertebrae, and movements involving forward bending of the spine magnify the loading on this already vulnerable part of the spine. In women with severe osteoporosis, this can trigger fractures, such as when e.g. a sneeze triggers a swift forward movement of the spine into flexion.

When it comes to rotation, however, there are no studies documenting risks of a simple twisting movement of the spine for people with osteoporosis. So, this begs the question, is there a biomechanical foundation for cautioning against twists?

This is an important question to explore, because most activities of daily living require rotation of the spine. In addition, there is some evidence that spinal movement in and of itself has a preventive function on vertebral fracture risk.

Most importantly, avoiding common spine movement, such as rotation, could trigger disuse atrophy, i.e. a weakening and eventual wasting of the muscles which occurs when muscles are no as active as usual. While disuse atrophy generally is caused by immobility, such as when a limb is in a cast, it is also known to develop if people stop performing their usual activities.

For all of these reasons, excessive caution against spinal rotation for people with osteoporosis—however well-intentioned—paradoxically might violate the primary maxim of the health practitioner: ‘Above all, do no harm.’

To get more clarity on this issue, and develop a clearer picture of how yoga affects vertebral fracture risk, it’s worth to take a closer look at the biomechanics of movement involving rotation and how this might affect the osteoporotic spine.

How Does Rotation Affect the Spine? Type I Vs. Type II Osteoporosis

According to Dr. Ray Long, an orthopedic surgeon and author of a series of yoga anatomy books, including The Key Muscles of Yoga, when considering the biomechanics of spinal rotation in people with osteoporosis, the different types of osteoporosis and which part of the vertebral body they affect need to be considered.

Type I osteoporosis, also known as postmenopausal osteoporosis, occurs before the age of 70, and it affects primarily the trabecular bone. The vertebral bodies are mostly trabecular bone surrounded by a thin rim of cortical bone. Trabecular bone is thus the inner part of the bone; it is a honeycomb like structure, which distributes forces through the bone.

Type II osteoporosis, also known as senile osteoporosis, occurs mostly after the age of 70. Type II osteoporosis affects both trabecular and cortical bone.

As trabecular bone is lost, regions with substantial amounts of trabecular bone become fragile and fracture prone, Dr. Long notes. This particularly includes the vertebral body, which is largely trabecular bone. Vertebral compression fractures mostly involve a collapse of the supporting trabecular bone on the inside of the vertebral body. Since the cortical bone is relatively thin, this loss of support can lead to fracture through it as well. This is in contradistinction to fragility fractures involving the wrist and hip, where the cortical support is weakened by Type II osteoporosis.

Importantly, biomechanically speaking, during rotation, the vertebral body is less affected than in flexion/extension movements.

“Force that would be tranmitted to the vertebral bodies, i.e. relatively small amounts of flexion/extension are likely absorbed by the intervertebral discs,” says Dr. Long. “In addition, the joint reaction forces, i.e. the force generated within a joint in response to movement, is transmitted to the facet joints and to some degree the transverse processes of the vertebrae.”

In other words, the forces created with rotation are less likely to affect the vertebral body, which is the vulnerable part of the spine in Type I osteoporosis due to trabecular bone loss.

“Type I osteoporosis affects almost exclusively trabecular bone as opposed to cortical bone. The facet joints and transverse processes, which do absorb much of the force during spine rotation, are composed predominantly of stronger cortical bone, as opposed to trabecular bone.” Dr. Long notes. “In other words, in Type I osteoporosis there is no apparent biomechanical foundation advising against twisting. The torsional force is not absorbed by the part of the vertebrae that has been weakened by loss of bone mass, i.e. the trabecular bone of the vertebral body.”

Less is known about the effects of rotation for senile Type II osteoporosis which typically occurs after the age of 70. Biomechanically speaking, it is possible that loss of cortical bone in the bones adjoining the facet joints could alter the strength of the facet joint during rotation, but there is no research indicating that this is the case.

Are Osteoporotic Fractures Due to Osteoporosis? The Role of Frailty

This provocative question was raised in a paper by European researchers some 20 years ago. Fracture risk, the paper argued, needs to be considered not just in terms of bone mineral density, but rather, more globally in the context of the relative degree of frailty in a person.

In fact, an increasing number of studies have found that frailty is a high risk factor for fractures, independent of osteoporosis as measured by bone mineral density.

Frailty is a syndrome, i.e. it is a multi-factorial condition characterizing people who have aged faster. Or put more specifically: In frail people, the age-related declines in function have advanced faster than in their age cohort. Frailty is characterized by lower muscle strength, diminished energy, lower physical ability and overall lower reserves. Frailty is more common in older people, but it can occur at all ages.

Frailty puts people at higher risk for dramatic changes in physical status and mental wellbeing, typically triggered by a sentinel event, such as a fall and fracture. So, not surprisingly, frailty has proven to be an independent predictor of all types of fractures—independent of osteoporosis.

A 2014 Canadian study of more than 9,000 people, for example, found that degree of frailty predicted fractures of the hip, vertebrae and all-type clinical fractures, irrespective of age and bone mineral density.

A 2016-meta-analysis of 1305 studies concluded that community-dwelling older people who were both pre-frail and frail had a higher risk of fractures. Another 2016-study found that as many as 70.8% of patients admitted to hospital with vertebral fragility fractures exhibited the frailty syndrome.

The frailty syndrome includes a number of factors: loss of bone mass (osteoporosis), loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia), poor nutritional status, physical slowness, and poor endurance.

This raises the question whether the fracture risk of osteoporosis occurs largely because osteoporosis is part of the larger syndrome of frailty? And, is frailty the missing link that explains why some people in a group of people with low bone mineral density incur fractures, while most do not?

The research on frailty is still in its early stages, so this will be a question for future research to determine.

However, for yoga teachers teaching people with osteoporosis and/or 65 and up, it’s important to identify individuals who may fall into the frailty category, and who are at higher risk for falls or fractures.

The 5 Characteristics of Frailty

Suspect frailty if at least three of the following five characteristics of frailty are present:

-

Muscle weakness,

-

physical slowness,

-

poor endurance (easily exhausted),

-

low levels of physical activity,

-

unintentional weight loss, i.e. loss of 10 lbs or 5% of body weight over last year).

Use an intake questionnaire for screening when teaching this age group, and consider teaching frail individuals in either private classes or a small group of 2-4 individuals max.

Do’s and Don’ts for Yoga for Osteoporosis

Women with osteoporosis—and the fitness trainers and yoga teachers that work with them—are between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, movement is essential for health, and strength-building exercise is particularly important for people with osteoporosis.

In addition, there is evidence suggesting that maintaining full spine mobility and moving the spine offers significant benefits and is important to prevent both vertebral fractures as well as other osteoporotic fractures.

At the same time, however, because of the ever-present risk of fragility fractures in women with osteoporosis, the natural tendency is to err on the side of caution and avoid movements that could be injurious.

When it comes to the body and movement, however, this is a risky proposition. The most basic rule governing the retention of bodily function is ‘What we don’t use, we lose.” Retaining healthy spinal articulation, trunk stability, and strong and flexible muscles—particularly those surrounding the spine—are all significant contributors to reducing fracture risk. It is also essential to prevent disuse atrophy and prevent people from developing the frailty syndrome.

So unless there’s a strong research foundation, proceed with caution when avoiding certain types of movement. In the case of flexion, there is biomechanical foundation and research evidence for urging caution.

When it comes to rotation, however, there is no research nor biomechanical evidence indicating that rotation could trigger vertebral compression fractures in otherwise healthy women with low bone density.

Still, when it comes to doing yoga with osteoporosis, special attention needs to be given to train the spine for optimum function, while avoiding mechanisms of injury.

This means that when teaching yoga to people with osteoporosis, form and alignment matters tremendously. How a yoga posture is done and the actions within the pose dictates its relative benefits and drawbacks, much more than the actual pose itself. Keeping this in mind, here are 6 recommendations to bear in mind when teaching yoga to people with osteoporosis.

6 Recommendations when Teaching Yoga to People with Osteoporosis

-

Teach the individual, not the pose. There is a vast range of capability within the 60+ age group. People who have stayed physically active generally retain most of their physical functions. In contrast, people with a sedentary lifestyle are likely to have poor coordination, low muscle strength, poor balance, etc. Yoga teachers teaching this group of people need to develop their skills to target instructions to be suitable for every body in the room, and not limit their teaching to a generic template for specific poses.

-

Rotation with Flexion of the Upper Spine Is Flexion. If doing twisting postures with a flexed upper spine, the pose involves flexion and therefore is subject to the biomechanical forces of flexion on the spine. The most common compensation yoga students make to counteract limitations in twisting range of movement is flexing the spine. When including twisting postures in your classes, spend ample time helping students develop the body awareness needed to avoid compensations in twisting postures.

-

Teach neutral spine. For proper alignment in yoga postures, it’s essential that students first learn how to sit, stand and move with a neutral spine preserving the curves of the spine. This will ensure that proper spinal alignment is carried over into yoga postures and flexion of the spine is avoided.

-

Be cautious with seated postures. Most students with tight hamstrings or hips are unable to sit with a straight spine in seated postures and create compensations by flexing. Unless you are confident that you can introduce modifications to avoid rounding of the spine, use this group of postures sparingly.

-

Engage the core. If alignment and the inner actions of the pose are good, Dr. Long notes, you don’t have to engage in large, forceful movement. Ease into positions, engage the core, anticipate the end point of the pose, and use core engagement to stabilize the spine while you’re headed towards the end point.

When teaching twists, dr. Long recommends, stabilize the core and twist once the core is stabilized. For example, in Marichyasana III where your knee is bent and you’re turning towards the knee, squeeze the thigh up against the torso to contract the psoas muscle. The psoas muscle works in conjunction with the quadratus lumborum muscles to stabilize the spine. As you engage the muscular stabilizers surrounding the spine,ß it will strengthen the muscles and protect the spine.

Featured Courses