View basket (0 items $0.00)

Error message

- Notice: unserialize(): Error at offset 5 of 154 bytes in variable_initialize() (line 1202 of /home/dh_6hcdc2/yogau.online/docroot/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- The file could not be created.

- The file could not be created.

Core Strength: How To Get Optimal Stability and Flexibilty in Your Core

What does core strength really mean, and why is it so important?

The most common misconception about core strength is that it merely means having strong abdominals—like the enviable washboard stomach achieved by developing your rectus abdominis muscle.

In truth, optimal core strength means having balanced flexibility, control, and power in all of the muscles in the core of your body: your abdomen, lower back, and waist. These muscles support your body in an upright posture and natural, efficient movement.

Core muscles have the potential to be very strong, and the spine to be extremely flexible. To move safely and efficiently, our core should be providing most of the support and be doing most of the work in the movement of the body. Our extremities should simply be extensions of what’s happening in our core.

If your core is out of balance in some way, you’re at risk for back pain, back spasms, disc problems, scoliosis, lordosis, kyphosis, sciatica, joint pain and injuries, and many other musculoskeletal conditions.

The Danger of Core-Strength Imbalance

First, since we’ve been using “core strength” as a broad term, let’s define how we actually want our core muscles to function. We want to be able to use our core muscles in their full range of motion, to be able to fully contract and fully release them as needed in order to do the movements that we want to do. In other words, we want control.

The dangers of having imbalances in the control of your core muscles are many; in fact, they can be blamed for nearly all functional musculoskeletal conditions. Let’s start with the most common one: back pain.

Many people develop chronically tight muscles in the lower back as a result of stress, heavy lifting, sitting or standing for long periods of time, or athletic training. Tightness in the lower back can actually make it more difficult to contract the abdominal muscles because the back muscles don’t want to get longer to allow the abdominal muscles to get shorter.

This can cause a vicious cycle in which the lower back muscles continually get overused and keep getting tighter because it is increasingly difficult to use the abdominal muscles. People with chronic, involuntary muscle tightness in their lower back are likely to experience muscle soreness and pain, back spasms, bulging and herniated discs, sciatica, and osteoarthritis in the lumbar vertebrae.

Having overly tight abdominal muscles can be just as dangerous. When the abdominal and thoracic cavities are constantly compressed, we are at risk for digestive problems, shallow breathing, high blood pressure, frequent urination, and even impotence.

Having overly tight abdominal muscles can be just as dangerous. When the abdominal and thoracic cavities are constantly compressed, we are at risk for digestive problems, shallow breathing, high blood pressure, frequent urination, and even impotence.

People with chronic tightness in the abdominal muscles also tend to develop kyphotic (rounded forward) posture over time. The muscles in the back and neck then have to work extra hard to keep them standing upright, and as a result, they often experience back and neck pain.

We should not be holding our abdominals tight all the time; we should simply be engaging them when necessary to support our posture and movement. When you learn to use your core muscles in a balanced way, then your proprioception and the resting level of tension in the muscles will keep you in a natural upright posture without you feeling as if you have to suck in your stomach or pull your shoulders back.

While it’s important to have balanced control of the muscles in the front and back of your core, don’t forget about the muscles on the sides. Your internal and external obliques, quadratus lumborum, latissimus dorsi, and erector spinae group work to bend your spine to the side and hike up your hips one at a time. If there is an imbalance in your use of these muscles, you are likely to develop scoliosis, functional uneven leg length, and hip and knee pain on one side.

When the use of our core muscles is out of balance in some way, not only do we experience problems in the core of our body but in our extremities as well. The joints and muscles of our arms and legs end up taking on more weight and range of motion than they are built to handle because they are compensating for the lack of movement, support, and control in the core. This is typically the cause of pain, recurring injuries, and joint degeneration in the hips, knees, shoulders, elbows, and neck.

Developing Balanced Control of the Core Muscles

If you have chronic muscle tightness or pain, a recurring injury, or a musculoskeletal condition (such as sciatica, scoliosis, or disc or joint issues), jumping right into a core-strengthening routine may make your condition worse. Strength-building exercises typically enhance our existing patterns. We tend to stay in our learned, dysfunctional muscular patterns unless we take the time to slow down and retrain our muscle memory.

So before you start building strength, you need to develop balanced control of your core muscles. Clinical Somatics exercises work with the nervous system to release involuntary muscle contraction, retrain proprioception, and increase muscular awareness and control. The exercises are an ideal way to regain control of your core so that you can stand and move in any way you want to—powerfully and without pain.

Building Core Strength

So, what are the best exercises to build core strength? The good news is that any full-body movement will improve your core strength if you consciously engage your core muscles and do the movement with good form. And if you have taken the time to develop balanced control of your core muscles, then moving with good form should come naturally.

General Rules for Improving Core Strength

-

Spend an equal amount of time working on all parts of your core unless you are making up for a lack of strength in one area. Make sure you are moving in all directions: forward, backward, bending to the sides and twisting to each side.

-

Always start by moving slowly and gently to warm up your body and remind your nervous system of exactly how you want to move. Once you have warmed up your body and mind, you’ll be ready to move more quickly and with more resistance.

-

Be sure to do all movements through your full range of motion so that you maintain complete control and do not develop chronic tightness in your muscles. Beware of typical strength-training exercises which tend toward shorter ranges of motion and fast movements. These types of exercises decrease range of motion and control—the opposite way we want to train our core.

-

Stay aware of your posture and movement as you move. Keep checking in with yourself to make sure you are using good form and that you are engaging your core muscles in a balanced way.

Be Aware of These Muscles

-

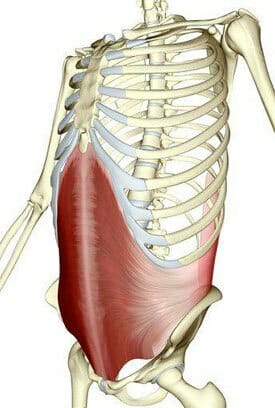

The abdominals consist of the rectus abdominis (the six-pack muscle), the internal and external obliques, and the transverse abdominis. All these muscles should be worked equally for optimal core stability. The transverse abdominis (shown right) is the one that will likely require the most conscious effort; it is engaged when hollowing out the belly.

-

To engage this muscle, lie on your back with your knees bent and feet on the floor.

-

Inhale down into your belly, then fully exhale and hollow out your belly.

-

When you’ve gotten the hang of this, try doing some slow, small crunches while keeping your belly hollowed out.

The Psoas Muscle

The psoas muscle is a very important muscle that flexes, rotates and adducts the hips, laterally tilts the pelvis and laterally flexes the spine. A tight psoas muscle is very often part of the problem in lower back and hip pain as well as a number of other conditions.

While it can be difficult to feel, control, and release the psoas, it is worth taking the time to explore this muscle. Releasing it can have dramatic effects on your posture and pain reduction, and gaining control of it will improve your core strength and stability tremendously.

Study with YogaUOnline and Christine Wushke - Fascia Awareness in Yoga & Movement: Keys to Enhancing Soft Tissue Resilience and Releasing Chronic Tension.

Reprinted with permission from Somatic Movement Center.com

Sarah Warren St. Pierre is a Certified Clinical Somatic Educator and the author of the book Why We’re In Pain. She was trained and certified at Somatic Systems Institute in Northampton, MA. Sarah has helped people with chronic muscle, and joint pain, sciatica, scoliosis, and other musculoskeletal conditions become pain-free by practicing Thomas Hanna’s groundbreaking method of Clinical Somatic Education. Sarah is passionate about empowering people to relieve their pain, improve their posture and movement, and prevent recurring injuries and physical degeneration.

Sarah Warren St. Pierre is a Certified Clinical Somatic Educator and the author of the book Why We’re In Pain. She was trained and certified at Somatic Systems Institute in Northampton, MA. Sarah has helped people with chronic muscle, and joint pain, sciatica, scoliosis, and other musculoskeletal conditions become pain-free by practicing Thomas Hanna’s groundbreaking method of Clinical Somatic Education. Sarah is passionate about empowering people to relieve their pain, improve their posture and movement, and prevent recurring injuries and physical degeneration.

Featured Courses