View basket (0 items $0.00)

Error message

- Notice: unserialize(): Error at offset 5 of 154 bytes in variable_initialize() (line 1202 of /home/dh_6hcdc2/yogau.online/docroot/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- The file could not be created.

- The file could not be created.

The Power of Healthy Breathing: Yogic Breathing, Posture and Diaphragmatic Dysfunction

If 20 years from now, I’m asked: “what did you do in the pandemic?” like many of us, I will be honor-bound to answer: I made sourdough bread. And, again, like many of us, I turned inward. Literally. For the past nine weeks, I’ve been studying my diaphragm.

Yes, I already knew the broad outlines: the diaphragm is our primary muscle of respiration, and it descends when we breathe in and ascends when we breathe out. But those were just words. Here are some things I didn’t know: how it felt when my diaphragm moved freely; why I so frequently reversed the action and lifted my chest when I breathed in; how the diaphragm works as a key muscle of core stability; what an immense effect it has on every abdominal organ; and finally, how relaxed a free diaphragm makes you feel.

That’s far too much to go into here.

Breathing is Automatic, But Healthy Breathing Might be Another Story

The most profound realization I’ve had is this: except under extreme circumstances, we don’t have to breathe. Under instructions from our autonomic nervous system, and with help from the intercostal muscles, the diaphragm does our breathing for us. When the diaphragm descends, the thoracic cavity becomes larger, the air pressure drops, and outside air rushes in. When the diaphragm rises, the thoracic cavity shrinks, the air pressure increases, and air flows out.

Our job, when we’re sleeping, sitting, or noodling around, is to do exactly nothing. And therein lies the problem. Most of us restrict our diaphragm and instead use muscles in our chest, shoulders, and neck when we inhale. That’s all very well when you’re out doing a half-hour of high-intensity interval training. You need all the oxygen you can get. Using the same muscles when you’re working at your desk is overuse and leads first to tension and then to pain.

Why do we do this? I suspect there are as many answers to this question as there are people. Some of us have been taught “breath control as a way to self-mastery” (9,860,000 results if you Google those words). We might have learned to take deep, chest-expanding inhalations or to breathe into our belly. Perhaps a traumatic event changed our breathing patterns, and the restricted patterns survived long after the trauma faded away.

Yogic Breathing Depends on Posture

No matter how our habit started, here’s one thing that keeps us breathing badly: modern posture. Just by adopting our cultural posture, we set ourselves up for diaphragm dysfunction.

If you want to free your diaphragm, the two things you must not do are: tuck your butt and lift your front ribcage. Not coincidentally, modern posture is defined by two main actions: tucking your butt and lifting your front ribcage.

(In the photo right, the yoga student stands with a lifted chest. If she relaxed her chest a bit, her diaphragm might move more naturally.)

Want to feel it? Try this:

-

Stand up, tuck your butt, or if you prefer, lift the front rim of your pelvis. Your belly will become tight. Notice whether or not your diaphragm can freely move down to inhale. Hint: no, it can’t.

-

Now, still standing, lift the front of your ribcage. You probably already lift to some extent, but this time, exaggerate the lift. And then take a deep breath by letting your diaphragm descend. Any luck? With your chest lifted, the only way to take a deep breath is to lift your chest even more.

Given that I spent roughly 65 years of my life in modern posture, it’s no wonder I had difficulty taking my theoretical knowledge of how the diaphragm moves and turning it into a felt experience.

How to Understand Diaphragmatic Movement

This might be the hardest part to grasp: the diaphragm works when it descends and relaxes when it rises.

I know I’m not alone in this. People generally work when they lift things and rest when they set them down. Especially in our own bodies, we “hold ourselves up” when we’re in “good” posture. When we relax, we let go and slouch.

And there’s one more very tricky cause: anatomical drawings.

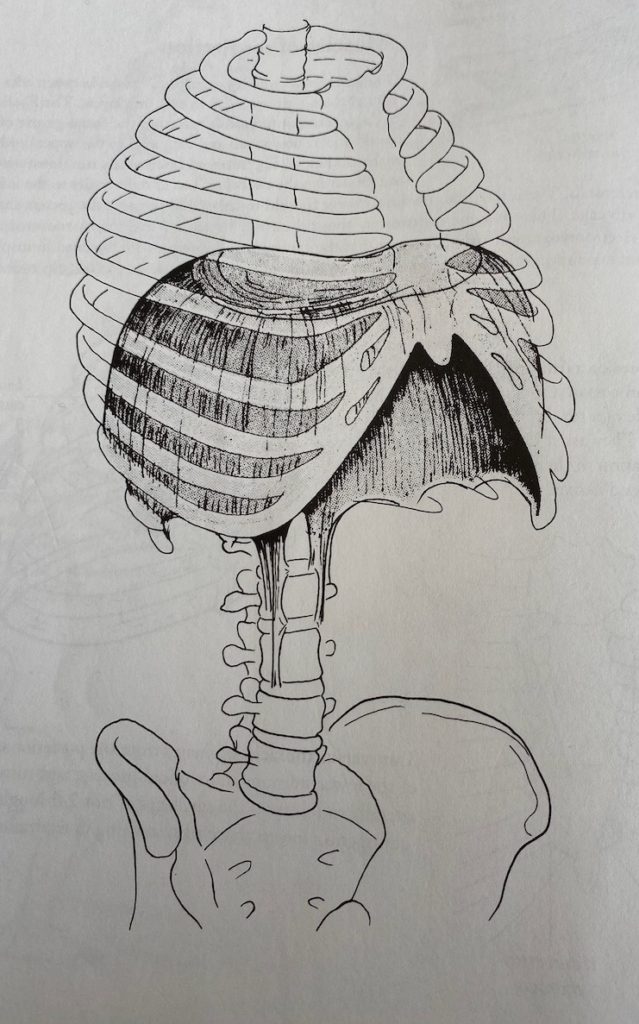

The clearest and most beautiful ones I know, like the one on the left, come from Anatomy of Movement by Blandine Calais-Germain. But in order to reveal the diaphragm, an anatomical drawing has to strip away everything that surrounds it, which gives the odd impression that the diaphragm works in splendid isolation, drifting down and floating back up again. (1)

In fact, the diaphragm separates our two main body cavities. The heart rests on it from above. Below, the diaphragm anchors the liver, spleen, and transverse colon.

Add the abdominal organs back into the picture, and all you will see of the diaphragm is a thin line at the bottom of the ribcage. To inhale, the diaphragm has to push against the abdominal contents. Breathing out is the rest phase, an effortless lift. (Check out this four-minute video below, Diaphragm Connections to Organs, by Dr. Kathy Dooley, for an illustrated tour.)

(In the anatomical drawing left- It looks like a dome floating free. But it isn't)

Diaphragm Connections to Organs

How Your Diaphragm Affects … Well … Everything

What’s so important about all this? It turns out that breathing with your diaphragm is high on the list of ways to improve your general health and lower your stress levels. That’s because restricting your diaphragm leads to a catalog of ills that includes sluggish digestion, back pain, and weak core muscles. Plus, if you habitually use your upper chest, shoulders, and neck muscles for breathing, you will create nagging pain and tension from a straitjacket of gripped muscles.

It’s now been four years since I stopped tucking my buttocks and lifting my chest. In that time, both my chronic shoulder tension and my mysterious intermittent stomach cramps have drifted away. As unrelated as they seemed at the time, I believe they were both caused by the same breathing pattern: underusing my diaphragm and overusing my shoulders. Now, I can’t help but see my chronic aches as siblings, the Hansel and Gretel of mysterious pains, holding hands as they departed.

These days my upper chest and shoulders stay still and soft as I inhale. On the exhalation, my diaphragm gives me a gentle internal lift. If I pay attention to it, I feel every breath cycle lengthening my lumbar spine. It’s a rise as sure and subtle as the air bubbles lifting my sourdough bread.

Reprinted with permission from Eve Johnson/Spinefulness.ca

Eve Johnson taught Iyengar Yoga for 18 years before being introduced to Spinefulness in 2016. Convinced by the logic, clarity, and effectiveness of Spinefulness alignment, she took the teacher training course and was certified in July 2018. Eve teaches Spineful Yoga over Zoom and offers an online Spinefulness Foundations course. For course information, go to http://spinefulness.ca.

References

1. https://bookshop.org/books/anatomy-of-movement-revised/9780939616572

Featured Courses