View basket (0 items $0.00)

Error message

- Notice: unserialize(): Error at offset 5 of 154 bytes in variable_initialize() (line 1202 of /home/dh_6hcdc2/yogau.online/docroot/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- The file could not be created.

- The file could not be created.

Empathy, Compassion and the Vagus Nerve

Most of us share a need to be seen and feel understood. We long to belong and to experience ourselves within the context of loving, nurturing relationships. When we have experiences of connection with other people, this helps to build a foundation for a loving and compassionate relationship with ourselves. This, in turn, can allow us to offer loving care to others. You can think of this exchange as an infinity symbol—a loving exchange of giving and receiving.

However, sometimes we do not receive this care and love in our relationships. Relational trauma impairs our trust in others and, like all traumatic events, is held in the body and is often maintained as dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The autonomic nervous system is the part of your nervous system that manages how you respond to stress. In addition, the autonomic nervous system also helps you to find healthy relaxation into a felt experience of safety. All of this is directly related to the tone and health of your vagus nerve.

The ability to express empathy and compassion is also related to the health of the autonomic nervous system. You might be someone who struggles with feeling “too much,” or you might have difficulty accessing your feelings. At either end of this continuum, working with your vagus nerve can help you to find the sweet spot of connection. One that allows you to compassionately attend to your own pain and relate to the pain of others (or the world) without becoming overwhelmed. Let’s take a closer look at empathy, compassion, and the vagus nerve.

Empathy and Highly Sensitive People

Empathy is a key element of the work that I do. As a psychotherapist, I am literally trained to not only listen to another but to sense and feel their experience with them. In truth, I’ve been this way my whole life—empathy is one of those traits that goes along with being a highly sensitive person.

My sensitivity also defined much of my childhood. You see, when I was growing up, I felt everything. If there was an emotion in the room, I was sure to pick up on it. Often the emotions would build up in me, and then I would start to feel anxious or overwhelmed or sad for “no reason.” It was easier when emotions were named by others. If someone was able to say “I’m sad” or “I’m angry,” then I didn’t take it on. But, it was a lot harder with other people’s “unexpressed” or “suppressed” emotions. You know what I mean: when someone has an angry tone of voice and expression on their face but denies it and says, “I’m fine!” This is where things got really confusing!

As a child, empathy was automatic and not something that I had a choice about. It was like a faucet left on full stream; I never knew that I could turn it down or off! As a result, there were times when I carried around a whole lot of emotional baggage. This could get pretty heavy. Sometimes I’d have big emotional meltdowns and not know why. Other times I’d get sick because all of these feelings left my body drained.

Developing an understanding of the vagus nerve helped me understand what was happening and how to adjust my empathy faucet.

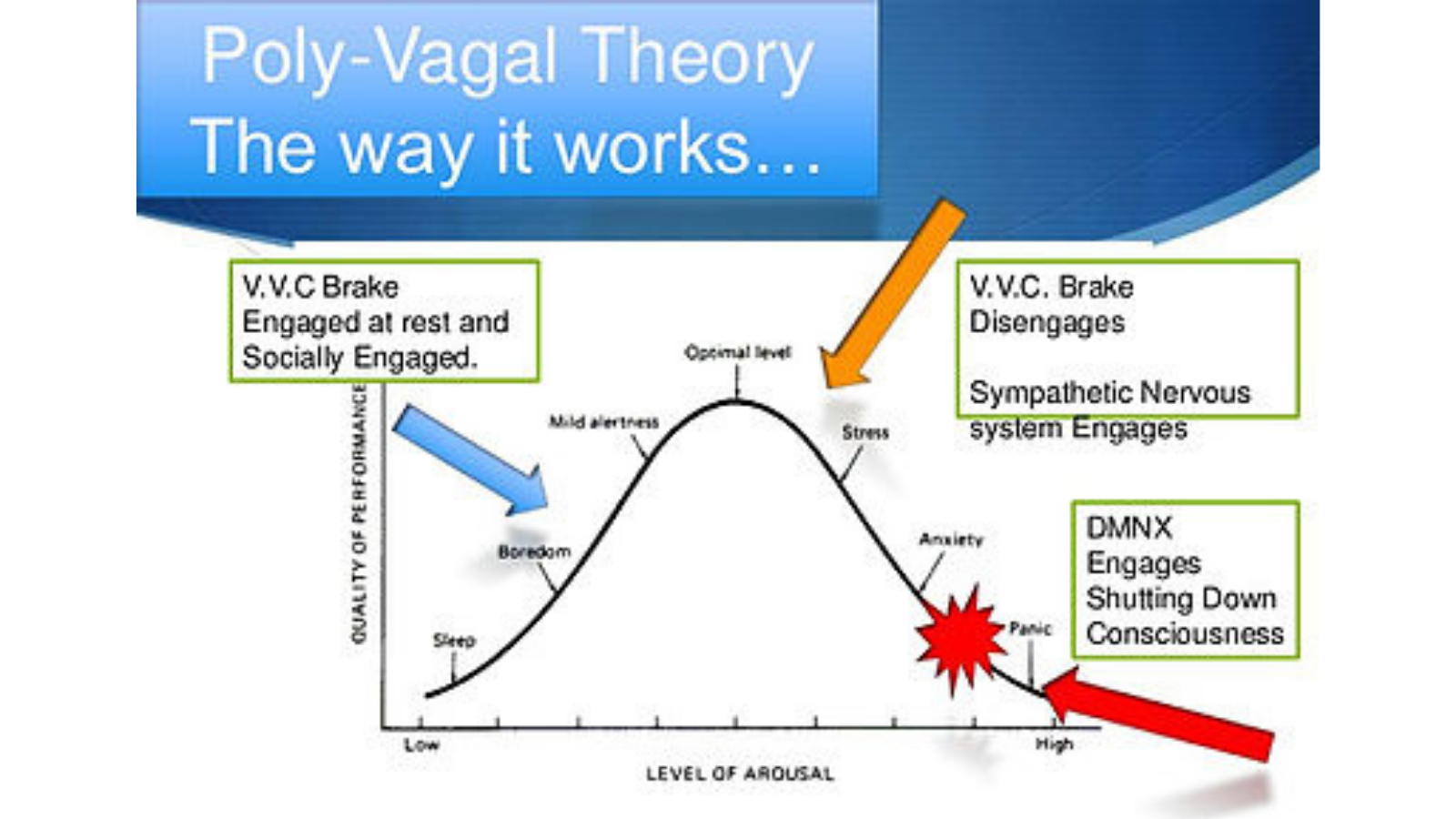

The Polyvagal Theory

The vagus nerve can be thought of as a mind-body information highway that communicates information about whether you are safe or in danger. The vagus nerve governs the nervous system’s parasympathetic response, and according to Dr. Stephen Porges, it comprises two vagal circuits.

Ventral Vagal Circuit

The first vagal circuit, which is the most recently evolved part of our vagus nerve, is called the ventral vagal complex. Porges also calls the ventral vagus the “social engagement system” because it connects to the muscles and organs above the diaphragm that are primarily involved in helping us feel socially connected and safe in the world.

The social engagement system gets its name because it is responsible for facial expressivity, which helps us understand or communicate emotions. In addition, the social engagement system is responsible for both the expressive and receptive domains of verbal communication. This guides the rhythm, tone, and inflection of our speech, which helps provide meaning to our communications.

Furthermore, the social engagement system enhances our ability to listen to others and allows us to pick up on emotional nuances within communications. We communicate a sense of care and kindness to others when we offer a soft smile that extends from our face and eyes or through a resonant tone in our voice that is then received by the ears of the listener. Given the connections between the vagus nerve and the heart and muscles of our face, we are also more likely to engage in caring responses.

Dorsal Vagal Circuit

The second vagal circuit is an evolutionarily older part of the parasympathetic nervous system called the dorsal vagal complex. Here, the vagus nerve extends below the diaphragm into the digestive organs. When we feel safe, the ventral vagal and dorsal vagal circuits coordinate a nourishing parasympathetic nervous system response that has an inhibitory effect upon the sympathetic nervous system. Indeed, this allows us to soften into a state of nourishing relaxation.

However, an evolutionarily older expression of the dorsal vagal complex can become dominant in situations of an ongoing threat from which there is no escape. This is an immobilization state of collapse associated with low muscle tone, slowed heart rate, nausea, dizziness, and numbness.

Putting on the Brakes

According to Porges’s model, both branches of the parasympathetic nervous system serve as a metaphorical “vagal brake” for the sympathetic nervous system, though they implement this brake in unique ways (Porges, 2011). It is akin to the process of putting on the brakes when driving a car: We can either slow down by pressing on the brakes smoothly, or we can slam on the brakes and come to a hard, fast stop.

The dorsal vagal complex functions like an abrupt brake by sending the body into a state of collapse and immobilization. In contrast, the social engagement system functions as a refined brake that facilitates increases in physical health and emotional wellbeing. Let’s explore how compassion and the vagus nerve are connected.

How to Distinguish Between Empathy and Compassion

Dysfunction in the vagus nerve can lead to excessive or unreasonable distrust, difficulty in conflict resolution, anger, aggression, or withdrawal from relationships. According to Dr. Porges (2017), having compassion for another person is dependent upon engagement of the vagus nerve however, empathy is not interchangeable with compassion.

Empathy often involves feeling someone else’s pain or negative emotion. This can feel threatening and may pull us out of our own center. As a result, our body begins to engage in defensive activation of the sympathetic nervous system. In short, too much empathy can be maladaptive.

On the other hand, compassion offers a calm vagal state, in which our “safety of self” projects acceptance toward the other. Compassion is based upon a principle that we respect both the suffering and joy of others, and we honor the other’s capacity to experience their own pain. Compassion is not driven by a need to “fix” another. Rather, we witness another without “sharing their pain.” Moreover, when we take over another person’s pain it can lead them to feel fear or shame.

Compassion is the neural basis for co-regulation. Compassion doesn’t mean non-action. However, our actions are wisely chosen ways to engage with others that don’t inadvertently suggest that they are broken or weak.

Compassion also rests upon a principle that we must start by attending to our own pain and suffering first.

How to Adjust the Empathy Faucet with Yoga, Breathing, and Understanding

Now that you understand how compassion and the vagus nerve are related, let’s take a look at how to adjust your empathy faucet. As an adult, I’ve learned to have a new conversation with my empathic self—actually a conversation with my young self. I’ve let myself know that I don’t have to carry the weight of the world, that it is okay to “let go,” and that it doesn’t really serve me to hold on anymore.

At times, I’ve had some interesting (and informative) replies back from my young self. She has said, “I don’t want to feel anything at all because when I do it’s just too much” or she has said, “But if I don’t take care of (feel) them I’ll be all alone!” I recognize that as a child, feeling for others was a way of connecting and that sometimes it was too much.

As an adult, I can now choose when and how much to sense and feel. I also give myself permission not to feel sometimes. I can honor my need to connect to others without having to take it all in. I get to have and honor my own boundaries. My empathy is no longer a faucet stuck on and I don’t have to turn off my gift.

Yes, there are still some days where I can sense that I am carrying the story or process of another person. In these times, I rely upon somatic tools of breath, movement, or yoga. I also rely upon an intention to give away what I am carrying. I give it over to something larger than myself—the earth, the universe, spirit, God.

I give it away so that I can simply be me.

Compassion and the Vagus Nerve

Our ability to access the healing power of the vagus nerve requires practice. In time, we can build the neural circuitry that supports self-compassion and our capacity to lovingly attend to others in relationships in a way that doesn’t drain our energy. In part, we can build this circuitry through mindfulness practices such as meditation or yoga. These help us reclaim the health of the autonomic nervous system.

Reprinted with permission from Dr. Arielle Schwartz.

Dr. Arielle Schwartz is a licensed clinical psychologist, wife, and mother in Boulder, CO. She offers trainings for therapists, maintains a private practice, and has passions for the outdoors, yoga, and writing. She is also the developer of Resilience-Informed Therapy which applies research on trauma recovery to form a strength-based, trauma treatment model that includes Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), somatic (body-centered) psychology, mindfulness-based therapies, and time-tested relational psychotherapy.

Resources:

Porges, S. W. (2017). ‘‘Vagal pathways: portals to compassion,’’ in The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science, ed. E. M. Seppala (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 189–202.

Featured Courses