View basket (0 items $0.00)

Error message

- Notice: unserialize(): Error at offset 5 of 154 bytes in variable_initialize() (line 1202 of /home/dh_6hcdc2/yogau.online/docroot/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- The file could not be created.

- The file could not be created.

What Causes Idiopathic Scoliosis?

Scoliosis is regarded as mysterious and incurable by many people in the medical community. While some scoliosis cases are caused by congenital structural abnormalities or neurological or muscular diseases, the vast majority—around 85 percent—are of unknown cause.

The fact is, the bones in our body do not move unless our muscles move them. And our muscles are controlled by our nervous system. So when our vertebrae move out of alignment in any way, they are being moved by our muscles, which are being controlled by our nervous system.

Many cases of idiopathic scoliosis are caused by chronically tight muscles pulling the spine out of alignment. If you have idiopathic scoliosis, you can touch your back and waist and feel how tight your muscles are.

If your nervous system is sending messages to your muscles to stay tight, no amount of passive lengthening (such as static stretching or massage) or forced realignment (such as bracing or chiropractic) will change these messages.

In this post, we’ll talk about the patterns of muscular contraction that are common in idiopathic scoliosis, how our natural motor learning process leads us to develop these patterns, and how pandiculation retrains the nervous system to release chronic, involuntary muscular contraction.

What is Scoliosis?

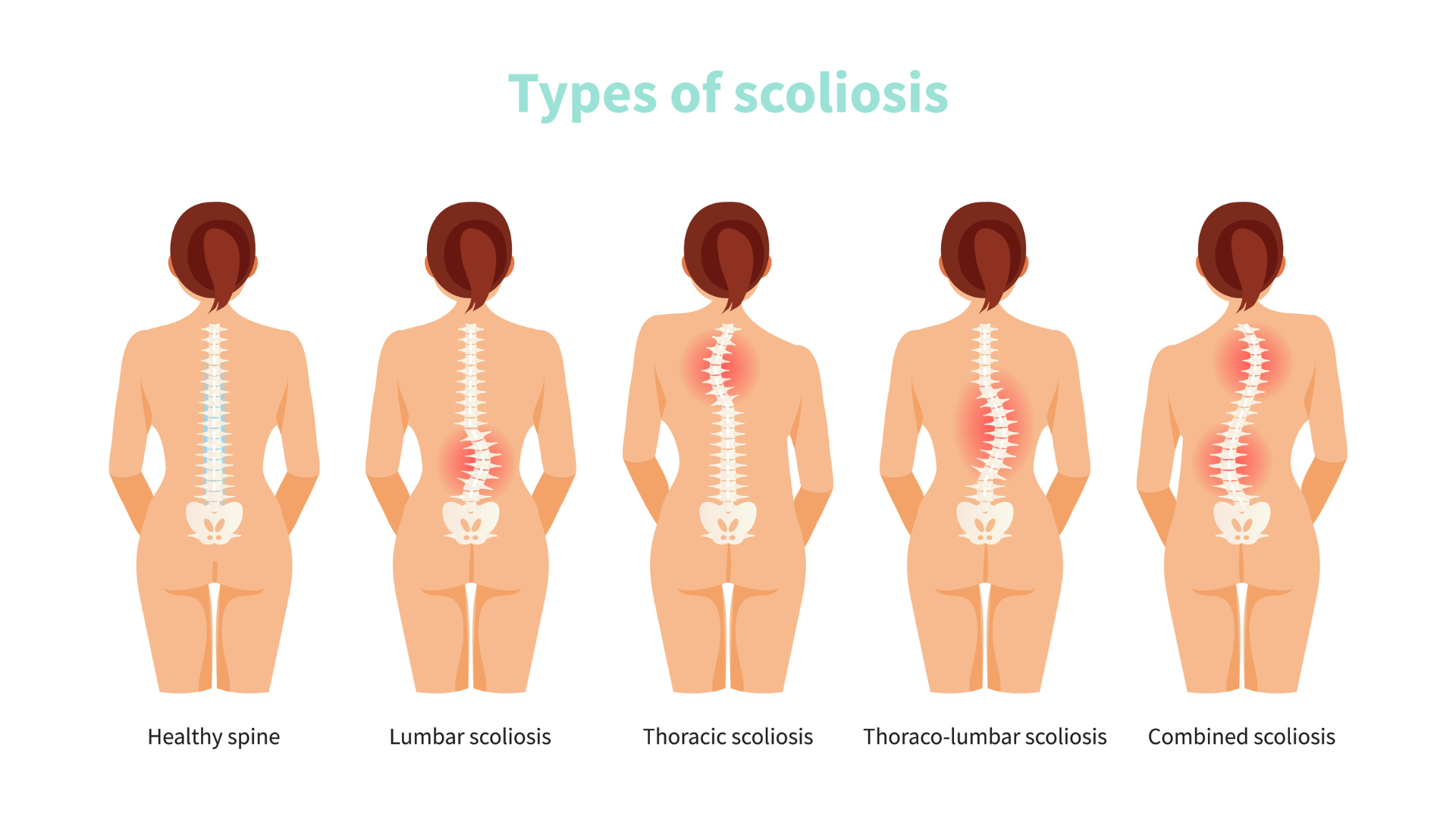

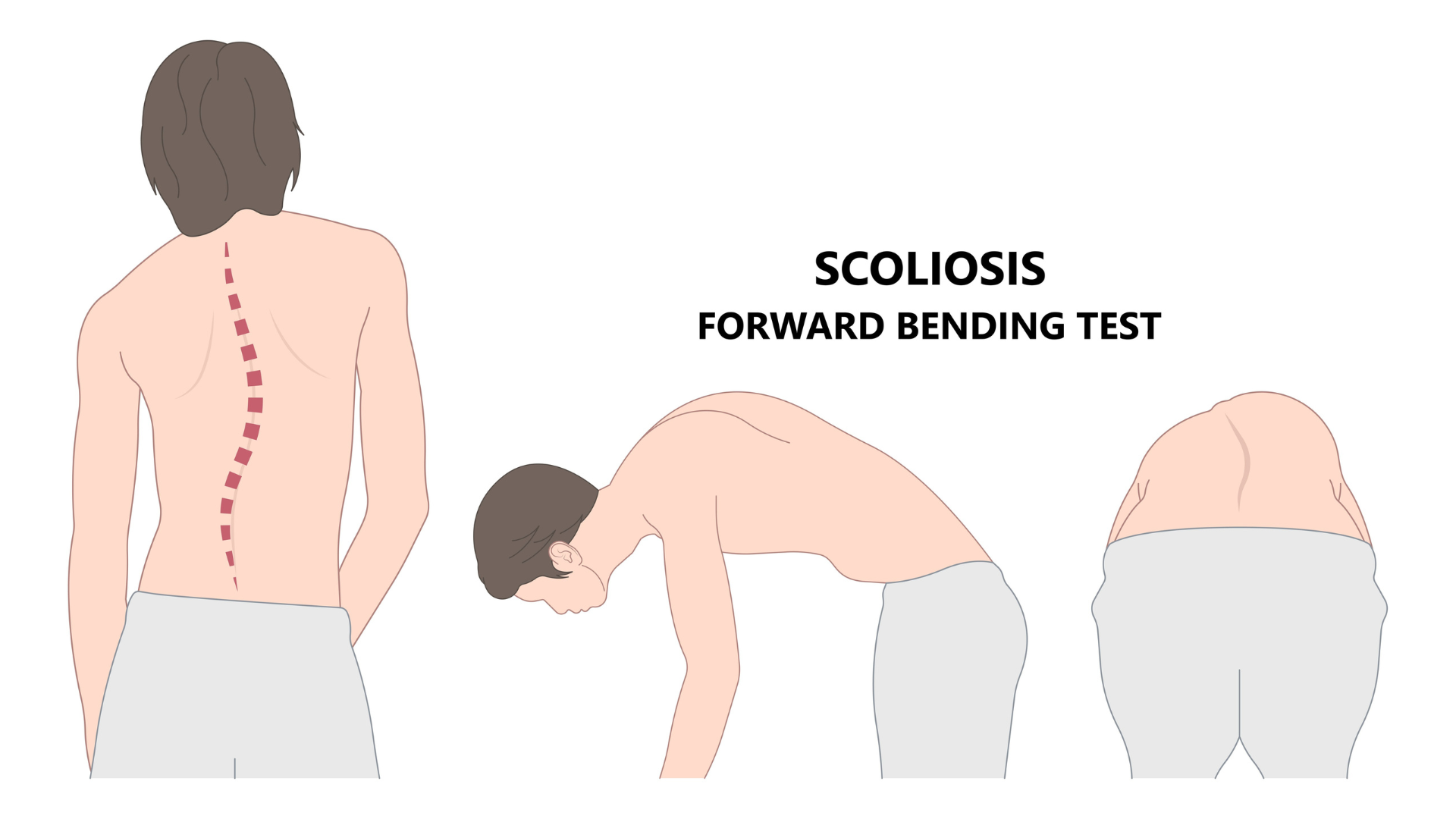

Scoliosis is a lateral curvature (side-bending) of the spine. A single curve in the spine is described as a C-curve. If the spine curves in both directions, it is described as an S-curve. If the degree of curvature is eleven degrees or more, it will be diagnosed as scoliosis.

Types of Scoliosis

Approximately 85 percent of scoliosis cases are classified as idiopathic (1) which means that the cause of the spinal curvature is unknown. In cases of congenital scoliosis, the spinal curvature is a structural abnormality that is present at birth.

Approximately 85 percent of scoliosis cases are classified as idiopathic (1) which means that the cause of the spinal curvature is unknown. In cases of congenital scoliosis, the spinal curvature is a structural abnormality that is present at birth.

In cases of neuromuscular scoliosis, the spinal curvature is caused by a neurological or muscular disease, such as cerebral palsy, spinal cord trauma, muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, spina bifida, neurofibromatosis, or Marfan syndrome.

What are the Side Effects of Scoliosis?

Roughly two-thirds of adults with scoliotic curves between 20 and 55 degrees experience back pain. (2 ) Many people with scoliosis develop pain in other parts of their bodies due to their postural misalignment, which puts uneven stress on the hips, knees, neck, and shoulders. Arthritis, disc and nerve compression in the spine, and difficulty breathing are also common.

Many people with untreated scoliosis, as well as some who have been surgically treated, develop spondylosis. (2) Spondylosis is an arthritic condition of the spine in which joints become inflamed, cartilage thins, and bone spurs develop. Disc degeneration or spinal curvature can lead to spinal vertebrae pressing on nerves, resulting in severe pain and requiring surgery.

Are Bracing and Surgery Effective?

Typically, bracing is recommended for curves greater than 25 degrees. Bracing attempts to slow or halt curve progression by forcibly aligning the spine. However, studies show mixed results when it comes to the efficacy of bracing (3) and some experts believe that the practice of bracing is outdated and ineffective. Patients who wear braces can also experience negative side effects such as pain, restricted breathing, and weakening or stiffening of their muscles due to lack of movement.

Typically, bracing is recommended for curves greater than 25 degrees. Bracing attempts to slow or halt curve progression by forcibly aligning the spine. However, studies show mixed results when it comes to the efficacy of bracing (3) and some experts believe that the practice of bracing is outdated and ineffective. Patients who wear braces can also experience negative side effects such as pain, restricted breathing, and weakening or stiffening of their muscles due to lack of movement.

When curves progress to 45 to 50 degrees or more, spinal fusion surgery is considered. About 38,000 people undergo spinal fusion surgery each year in the United States. (4) In spinal fusion surgery, metal rods, hooks, wires, and screws are attached to the spine in order to force it into a straight position. Then doctors attach pieces of bone, which grow together and create the actual fusion of the spine.

Patients who undergo this type of surgery lose 20 to 60 percent of their spinal flexibility. (5) A great deal of strain is put on the unfused parts of the spine, leading to a high rate of disc degeneration and osteoarthritis. Research shows that 75 percent of patients experience degeneration in their sacroiliac (SI) joints after spinal fusion surgery.6 And sadly, more than 40 percent of spinal fusion patients experience no reduction in their pain levels. (5)

Surgery Comes with Complications

Rates of complications in spinal fusion surgeries vary, but are quite high across the board. Some research has shown that more than half of the surgeries are unsuccessful, meaning that the vertebrae do not actually fuse. Even though the vertebrae are held in place by hardware, contraction patterns in the back muscles cause micromovements in the spine, preventing the continuous growth of the bone.

Muscular contraction can be so strong that metal rods inserted along the spine actually break, causing a great deal of pain and requiring repeat surgery. Given the high risk of complications and the lack of evidence supporting spinal fusion as an effective treatment, many doctors and researchers now agree that the surgery can be used to slow or halt the progression of the curvature, but little else.

Idiopathic Scoliosis and Aging

A 2014 review published in American Family Physician found that approximately 85 percent of scoliosis cases are classified as idiopathic or of unknown cause. (1) So, 85 percent of the people who get diagnosed with scoliosis get no explanation as to what has caused it.

A 2014 review published in American Family Physician found that approximately 85 percent of scoliosis cases are classified as idiopathic or of unknown cause. (1) So, 85 percent of the people who get diagnosed with scoliosis get no explanation as to what has caused it.

The same review found that between 2 percent and 4 percent of teenagers have scoliosis. According to a retrospective study done at Johns Hopkins University, the rate of scoliosis increases to more than 8 percent in adults over the age of 40. (7) And a 2005 study of 75 healthy adults over the age of 60 with no previous diagnosis of scoliosis or spinal surgery found the rate of scoliosis to be 68 percent. (8)

This increasing prevalence with age indicates that muscular contraction from repetitive activities, injury, and stress—the effects of which increase with age—play a role in developing the condition.

Muscular Patterns and Idiopathic Scoliosis

Our spine can flex (bend) in all directions: forward, backward, and to each side. When we bend in any direction, we can rotate our spine to either side as well. Since we have 24 articulating (moving) vertebrae in our cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine and many different muscles that control the movement of our vertebrae, we can develop varied, unique patterns of spinal flexion and rotation.

Our spine can flex (bend) in all directions: forward, backward, and to each side. When we bend in any direction, we can rotate our spine to either side as well. Since we have 24 articulating (moving) vertebrae in our cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine and many different muscles that control the movement of our vertebrae, we can develop varied, unique patterns of spinal flexion and rotation.

Scoliosis is never as simple as a single sideways bend or curve in the spine. We always compensate or balance ourselves out by developing other muscular patterns, like rotating to one side, arching our back, or rounding forward.

Let’s talk about some of the most important muscles involved in scoliosis.

-

Muscles That Move the Spine

-

Muscles that Laterally Bend the Spine

The biggest, strongest muscles in our core that flex our spine laterally are our internal and external obliques. Our obliques also rotate our spine, so any chronic tension in our obliques will likely create both a lateral curve and some degree of rotation.

The intertransversarii are small, short muscles that connect each individual vertebrae to the vertebrae above and below it in the cervical and lumbar portions of the spine. These little muscles laterally flex the cervical and lumbar spine. Since they are the deepest muscles in the neck and lower back, they are nearly impossible to touch or sense internally.

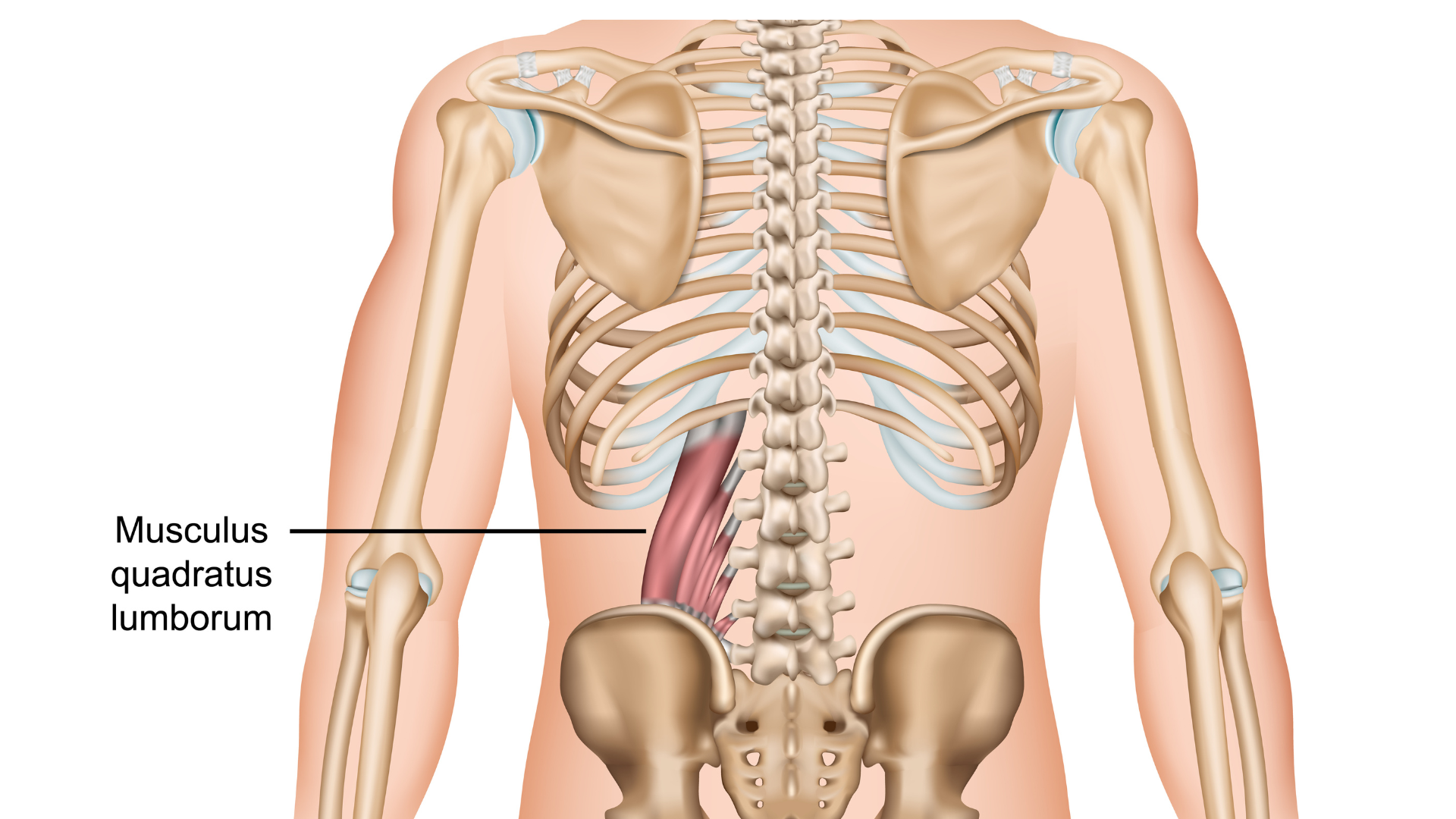

We think of the quadratus lumborum (QL) as a lower back muscle, but technically, it’s our deepest abdominal muscle. The quadratus lumborum attaches our lowest rib to the top of our pelvis, and connects to our first through fourth lumbar vertebrae. This strong muscle laterally flexes our spine to either side, laterally tilts our pelvis (hikes our hips up one at a time), and helps to extend our spine. So, chronic tension in the quadratus lumborum not only contributes to lumbar scoliosis but also to functional leg length discrepancy and hyperlordosis.

Muscles that Extend the Spine

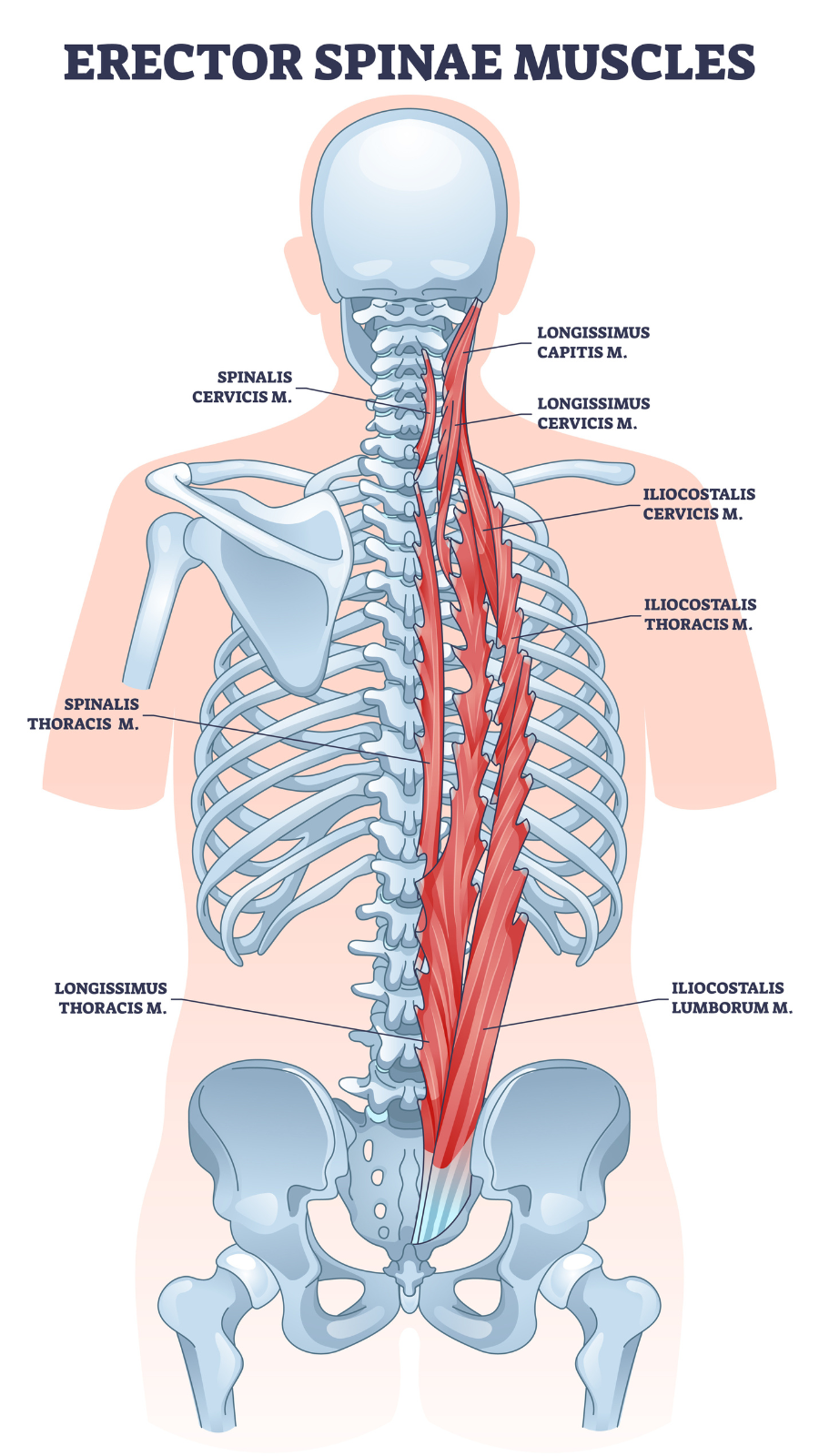

The erector spinae group of muscles travels from the base of the skull and cervical vertebrae all the way down to the pelvis, attaching to each vertebrae and rib. This group of muscles both laterally flexes the spine and extends it, meaning that it arches the back. So, chronic tension in these muscles can create both scoliosis and hyperlordosis, or an exaggerated arching of the lower back.

The erector spinae group of muscles travels from the base of the skull and cervical vertebrae all the way down to the pelvis, attaching to each vertebrae and rib. This group of muscles both laterally flexes the spine and extends it, meaning that it arches the back. So, chronic tension in these muscles can create both scoliosis and hyperlordosis, or an exaggerated arching of the lower back.

Muscles That Generate More than One Action

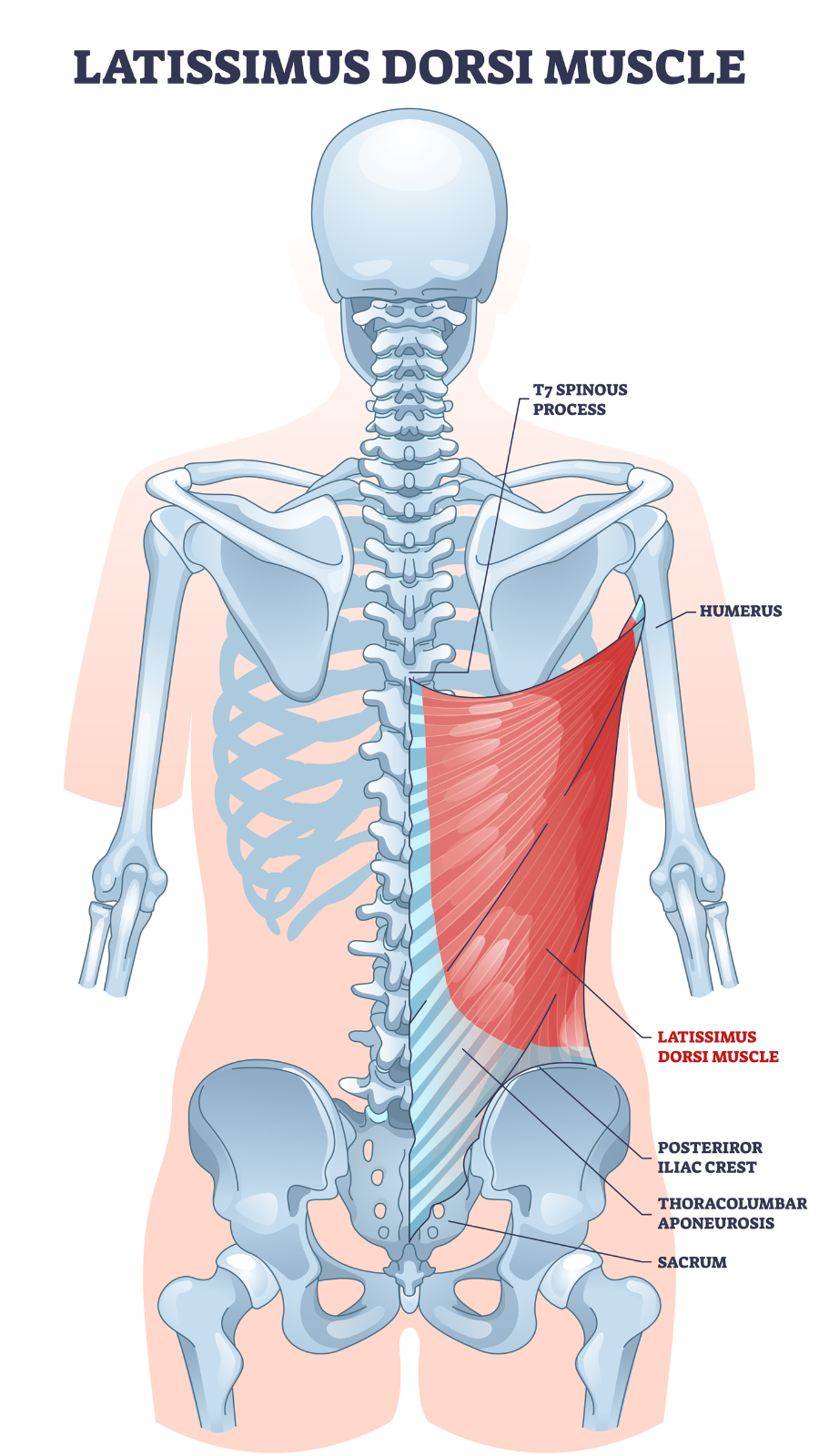

The latissimus dorsi is the broadest muscle of the back, spanning from the lumbar and lower half of the thoracic spine all the way to the upper arm just below the shoulder joint. The latissumus dorsi participates in many actions: extending, adducting, and medially rotating the shoulder, laterally flexing the spine, extending the spine, and even tilting the pelvis forward or to the side.

The latissimus dorsi is the broadest muscle of the back, spanning from the lumbar and lower half of the thoracic spine all the way to the upper arm just below the shoulder joint. The latissumus dorsi participates in many actions: extending, adducting, and medially rotating the shoulder, laterally flexing the spine, extending the spine, and even tilting the pelvis forward or to the side.

The transversospinalis group of muscles are small muscles in between each vertebrae, similar to the intertransversarii. But this group of muscles rotates and extends the spine, contributing to both scoliosis and hyperlordosis.

It’s Never Simple

The most important thing to take away from this discussion is the fact that the muscular patterns involved in scoliosis can be very complex. All of the muscles in the core of the body, including some we haven’t mentioned, will be involved in the lateral flexion, rotation, and extension or forward flexion of the spine, as well as in the compensatory patterns we develop to balance ourselves out.

The result of so many multi-functional muscles being involved is that idiopathic scoliosis typically involves lateral flexion to one or both sides, rotation to one or both sides, and either or both extension and forward flexion. These turns and twists can occur at various parts of the spine, creating patterns of spinal curvature as unique as we are.

Reprinted with permission from Somatic Movement Center.

Sarah Warren St. Pierre is a Certified Clinical Somatic Educator and the author of the book The Pain Relief Secret. She was trained and certified at Somatic Systems Institute in Northampton, MA. Sarah has helped people with chronic muscle and joint pain, sciatica, scoliosis, and other musculoskeletal conditions become pain-free by practicing Thomas Hanna’s groundbreaking method of Clinical Somatic Education. Sarah is passionate about empowering people to relieve their pain, improve their posture and movement, and prevent recurring injuries and physical degeneration.

Sarah Warren St. Pierre is a Certified Clinical Somatic Educator and the author of the book The Pain Relief Secret. She was trained and certified at Somatic Systems Institute in Northampton, MA. Sarah has helped people with chronic muscle and joint pain, sciatica, scoliosis, and other musculoskeletal conditions become pain-free by practicing Thomas Hanna’s groundbreaking method of Clinical Somatic Education. Sarah is passionate about empowering people to relieve their pain, improve their posture and movement, and prevent recurring injuries and physical degeneration.

Resources

1. Horne, J.P., R. Flannery, and S. Usman. (2014) “Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Diagnosis and Management.” American Family Physician 89, no. 3: 193–198.

2. Shah, S.A., MD. “Scoliosis.”

https://www.nemours.org/content/dam/nemours/wwwv2/filebox/

service/medical/spinescoliosis/scoliosisguide.pdf

3. Davies, E., Norvell, D., and Hermsmeyer, J. (May 2011). “Efficacy of bracing versus observation in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis.” Evidence-Based Spine-Care Journal; 2(2): 25–34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3621850/

4. Information and Support. National Scoliosis Foundation. http://www.scoliosis.org/info.php

5. Weiss, H.R. and Goodall, D. (August 2008). “Rate of complications in scoliosis surgery – a systematic review of the Pub Med literature.” Scoliosis, 3, 9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2525632/

6. Ha, K.Y., Lee, J.S., and Kim, K.W. (May 2008). “Degeneration of sacroiliac joint after instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: a prospective cohort study over five-year follow-up.” Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 33(11):1192-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18469692

7. Kebaish, K.M., et al. (April 2011) “Scoliosis in Adults Aged Forty Years and Older: Prevalence and Relationship to Age, Race, and Gender.” Spine (Phila PA 1976) 36, no. 9:731–736.

8. Schwab, F. et al. (2005). “Adult scoliosis: prevalence, SF-36, and nutritional parameters in an elderly volunteer population.” Spine (Phila PA 1976), May 1; 30(9):1082-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15864163

Featured Courses