View basket (0 items $0.00)

Error message

- Notice: unserialize(): Error at offset 5 of 154 bytes in variable_initialize() (line 1202 of /home/dh_6hcdc2/yogau.online/docroot/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- The file could not be created.

- The file could not be created.

How Well Are You Aging? An Easy Test of Health and Longevity - Explorations in Spatial Medicine I

How healthy is your body? And, how well are you aging?

The more we know about the health of our body and early warning signs of breakdown or distress, the more we are able to take steps to prevent or counteract minor issues that could turn into major ailments down the road.

We are all familiar with measuring blood pressure, Body Mass Index, DEXA scans, blood sugar levels, and so on. These are some of the tests that help us keep tabs on what’s going on in and with our bodies as we get older. But most of these involve a visit to your doctor and only give an impression of one aspect of your health.

Here’s an easy test you can do for yourself: Measure your height.

People get shorter as they get older. Most of us think of this as just an irrelevant fluke. However, research suggests that the loss of height can say something important about how well your body is aging. While minor height loss is nothing to be concerned about, research shows that significant height loss, i.e., more than an inch, as we get older, can be linked to greater health risks.

Height Loss Linked to Increased Mortality

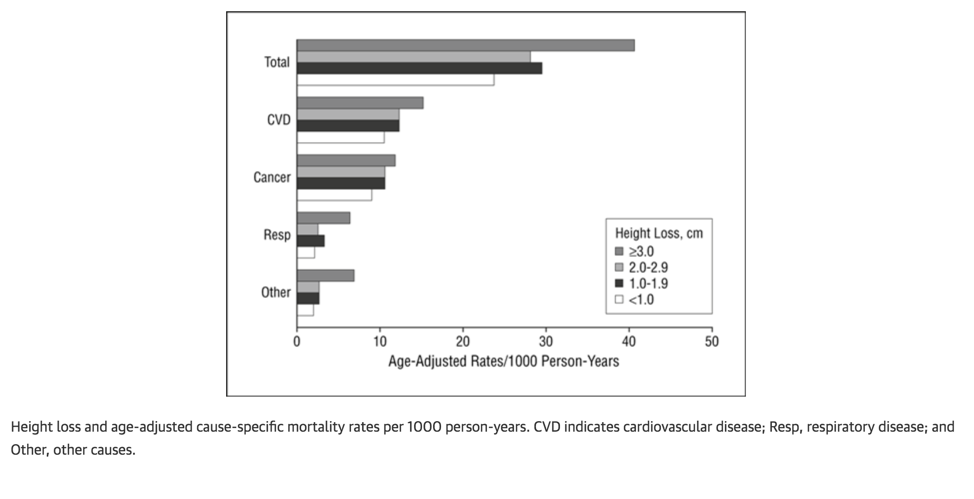

In one study, which was performed as part of the large British Regional Heart Study, researchers looked at height loss in 4,213 men over a 20-year period, from they were aged 40 to 59 till they were aged 60-79 years. The study isolated the men who had lost the most height, in this case, more than 3 cm or a little over an inch.

The researchers found that the men who had lost more than 3 cm (2.54 cm – 1 inch) were 64 percent more likely to die than those who had lost less than one cm in height, or less than half an inch.

Many of the additional deaths in the group of men who had lost the most height were due to cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, or other non-cancer diseases. Height loss was associated with a 42 percent increased risk of heart problems, such as heart attacks, even in men who had no history of cardiovascular disease. The study was published in a 2006 issue of Archives of Internal Medicine.

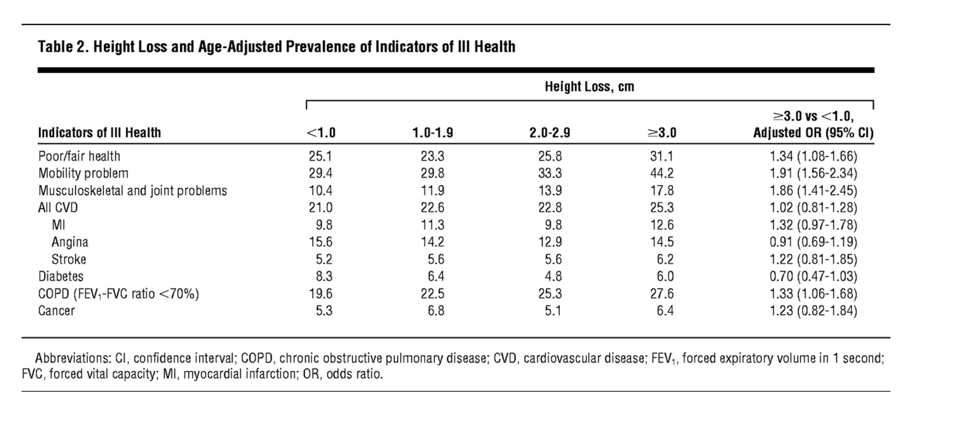

The researchers also found that the greater the loss of height, the more the person in question was likely to suffer from mobility problems, musculoskeletal issues (e.g., back pain), joint problems, and be in overall poor health (see Table 2 below).

The researchers also found that the greater the loss of height, the more the person in question was likely to suffer from mobility problems, musculoskeletal issues (e.g., back pain), joint problems, and be in overall poor health (see Table 2 below).

Greater height loss was also linked to co-morbidities like cardiovascular disase, diabetes, cancer, and chronic lung disease.

Another study followed 4,000 elderly men and women in Hong Kong with a mean age of around 72.5 over a four-year period. The researchers found that those who continued to lose height, in this case more than 2 cm, had more health problems, and they were more likely to die early.

For men, the problems associated with greater height loss were fractures and death from respiratory disease. For women, the loss of height was linked to accelerated bone loss and more overall fractures.

Other studies on younger populations have shown similar results.

How Does Height Loss Affect Our Health?

The first question that comes to mind after reading these results, of course, is why height loss would be correlated with the incidence of disease and increased mortality. So far, unfortunately, the exact mechanics of how this connection comes about are not known.

One possible factor could be osteoporosis: Osteoporosis is known to cause loss of height, and it is linked to higher mortality. However, according to the researchers in the above study, height loss resulting from osteoporosis is generally greater than 6.0 cm – more than two inches – particularly when vertebral fractures are present.

In the present study, however, even men with a height loss of 3.0 to 4.0 cm had greater mortality. The researchers also didn’t find a link between height loss and smoking or with precursors to coronary heart disease, such as hypertension, high cholesterol, inflammation, or diabetes.

One potential explanation, the researchers note, could also be the loss of skeletal muscle mass that happens with aging. A.k.a. sarcopenia, loss of muscle mass has also been shown to be a predictor of mortality, and like height loss, it is associated with lower body weight and weight loss, low albumin levels (a marker of undernutrition), physical inactivity, chronic lung disease, and mobility limitations

In addition, one can speculate that the following mechanisms could also be at play. The loss of height could pose a health issue because it may affect the normal functioning of the respiratory system and the gastrointestinal system. This, in turn, may lead to lower appetite and, consequently, poor nutritional status and even weight loss. It is also possible that the loss of height will depress the ribcage and thereby the lungs and heart cavity, starving the body for oxygen and restricting the heart’s ability to pump blood freely.

Why Do We Lose Height and What Can You Do About It?

Height loss is related to age-related changes in the muscles, bones, joints and changes in the spine, particularly the intervertebral discs.

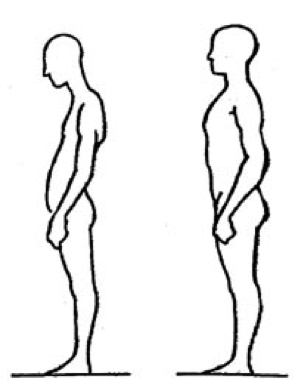

Height loss is also related to posture changes, inactivity, and loss of height in the arch of the foot, and as noted above, for people with osteoporosis, it can be caused by vertebral compression fractures.

Still, there are some key age-related changes that are more common and contribute more than others. Some researchers believe that sarcopenia, or loss of skeletal muscle, may be a key factor. Loss of skeletal muscle, a.k.a. sarcopenia, affects everyone over the age of 50, but muscle loss particularly accelerates after the age of 60. From the 50s, most people lose muscle mass at an estimated rate of 1-2% per year. After the age of 60, muscle loss may accelerate to as much as 3% per year.

Everyone loses some muscle mass as they age, but the threshold for sarcopenia is reached once a person’s muscle mass falls below two standard deviations of the mean of the average for a young person, and gait speed slows below a certain threshold (0.8 m/second is a standard measure). Researchers estimate that 5–13% of people aged 60–70 years have sarcopenia; for 80 year olds, the range is 11–50%.

Poor muscle strength and loss in skeletal muscle mass with aging have been shown to be predictors of mortality. Height loss is also associated with the same factors as sarcopenia: i.e., lower body weight and weight loss, low albumin levels (considered a marker of undernutrition), physical inactivity and mobility limitations, and respiratory difficulties, which also are predictors of mortality.

In short, loss of muscle mass is one underlying factor that may contribute to bone loss, loss of posture health, poor joint health, and loss of structural integrity, i.e., reduced health of the spine and back and poor balance. All of these are associated with a greater risk of fractures. In the elderly, fractures, particularly hip fractures, are one of the greatest risk fractures for disability or death.

Another factor that may be involved in height loss is the gradual loss of hydration of the intervertebral discs that separate and cushion the vertebrae of the spine. After the age of 25, the discs begin to lose moisture and, as a result, shrink, much like a sponge drying up, will diminish in size.

Height Loss, Compression and Health: The Effect on Body Cavities

Another factor to consider when looking at the link between height loss and poor posture on health is the effect of height loss on body cavities.

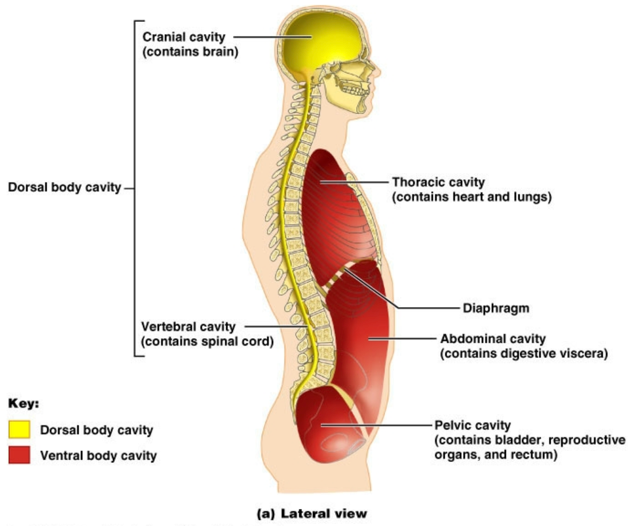

The human body has two main body cavities: The dorsal cavity and the ventral cavity. The dorsal cavity, in turn, contains the brain (in the cranial cavity) and the spinal cord (in the vertebral cavity). The ventral cavity, in turn, contains the heart and lungs (in the thoracic cavity), the digestive organs and kidneys in the abdominal cavity, and finally, the bladder and reproductive organs in the pelvic cavity.

The human body has two main body cavities: The dorsal cavity and the ventral cavity. The dorsal cavity, in turn, contains the brain (in the cranial cavity) and the spinal cord (in the vertebral cavity). The ventral cavity, in turn, contains the heart and lungs (in the thoracic cavity), the digestive organs and kidneys in the abdominal cavity, and finally, the bladder and reproductive organs in the pelvic cavity.

The cavities are, as the name implies, empty spaces. However, they perform important functions. The cranial cavity cushions and protects the brain, and the other cavities similarly cushion and protect the internal organs.

Importantly, because the lungs, heart, and even digestive and reproductive organs expand and contract, the cavities have to be flexible to allow for the free function of the organs.

Importantly, because the lungs, heart, and even digestive and reproductive organs expand and contract, the cavities have to be flexible to allow for the free function of the organs.

The cavities, in other words, are the seat of some of the body’s most important real estate. Yet, with deteriorating posture and height loss, the cavities lose their integrity, and this results in the compression of the internal systems.

While this issue is not commonly discussed in modern allopathic medicine, osteopaths and bodyworkers point to the visceral compression that arises with the loss of posture balance.

One of the early proponents of this theory was Joel E. Goldthwait, Chief of Orthopedic Surgery in Boston, in the early 1900s. Goldthwait believed that many chronic diseases could be linked to compromised organ function caused by body misalignments.

It’s pretty obvious that standing or sitting badly can impact the health of the spine and joints, but he was one of the first to point out that organ health is impacted as well. If organ position is compressed or sagging, he noted, it will lead to compromised bodily functioning in the long run.

“The main factors which determine the maintenance of the abdominal viscera in position are the diaphragm and the abdominal muscles, both of which are relaxed and cease to support in faulty posture.

The disturbances of circulation resulting from a low diaphragm and ptosis (sagged abdomen) may give rise to chronic passive congestion in one or all of the organs of the abdomen and pelvis, since the local as well as general venous drainage may be impeded by the failure of the diaphragmatic pump to do its full work in the drooped body.

Furthermore, the drag of these congested organs on their nerve supply, as well as the pressure on the sympathetic ganglia and plexuses, probably causes many irregularities in their function, varying from partial paralysis to overstimulation.

All these organs receive fibers from both the vagus and sympathetic systems, either one of which may be disturbed. . . . These disturbances, if continued long enough, may lead to diseases later in life.

. . . . . When the human machine is out of balance, physiological function cannot be perfect; muscles and ligaments are in an abnormal state of tension and strain. A well-poised body means a machine working perfectly, with the least amount of muscular effort, and therefore better health and strength for daily life.” In Joel E Goldthwaith Body Mechanics in Health and Disease

In modern times, Goldtwhwaith’s work is echoed by British osteopath Leon Chaitow as well as Canadian researcher Wolf Schamberger, a Professor of Sports Medicine at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

In this work on the ‘malalignment syndrome,’ Schamberger points to the biomechanical fallout of misaligned body parts. Schamberger focuses less on organ function and more on the biomechanical changes prompted by the shift in weight-bearing and the resulting asymmetries in muscle tension, joint integrity, and so on.

Explorations in Spatial Medicine - How Structure Affects Our Health, Wellbeing, and Longevity

The impact of height loss on health and mortality is just one example of how structure affects our health and well-being. It is one expression of what Anatomy Trains author Tom Myers refers to as 'Spatial Medicine."

Spatial medicine focuses on the impact on the health of the structural relationships of the body, particularly on the role of the fascia, the all-pervasive connective tissue of the body, which is responsible for holding the structures of the body together. Restrictions or adhesions in certain parts of the fascial network create tensional patterns throughout the entire system.

Such tensional patterns are distributed throughout the network and often lie at the root cause of pain issues. However, because it is a distributed system of tensional patterns, the pain may manifest in a different part of the body than where the original restriction resides. For this reason, treating the symptom, i.e., focusing directly on the seat of pain, often proves ineffective because the root cause lies elsewhere.

Spatial medicine focuses on restoring the health of the soft tissues and facilitating the release of chronic tensional patterns in the body. Myers notes that yoga, Pilates, and bodywork are at the forefront of this work. We are really only in the beginning stages of what this important work can contribute to our approaches to fostering health and healing going forward.

Through the practices of yoga and bodywork, spatial medicine focuses on releasing restrictions to systematically recreate and maintain space and fluidity of bodily structures, enabling the systems and functions of the body to work more efficiently. This opens a new approach to healing that we're only beginning to understand and explore, notes Myers.

The Ultimate Yoga Back Care System: Keys to Improving Posture, Preventing Back Pain, and Resetting Your Aging Trajectory

Featured Courses