View basket (0 items $0.00)

Hyperkyphosis: The Cause and the Solution

Many years ago, my husband Alan, our friend Jerome and I took a trip to our property on a northern gulf island.

We planned to stay in another friend’s cabin while Jerome and Alan put Jerome’s cabin up on jacks and replaced the rotting foundations. We arrived, let ourselves in, and went out on the back deck to look at the lake and savor the moment. We heard the deck door shut behind us and realized that we were locked out.

The deck cantilevers out from the side of the cabin. It’s a substantial drop from the deck to the ground, and there aren’t any stairs down. We spent some time trying to open the door, then, after weighing the odds, Alan climbed over the railing, slid down a column, opened the deck door, and let us back in.

Right about then, we discovered that one of the windows on the deck was unlocked.

(If hyper-kyphosis is a consequence of aging, what’s happening here?)

Is Hyperkyphosis Inevitable?

How does this story possibly relate to hyperkyphosis—the medical term for an overly rounded upper back?

Well, if we hadn’t fixated on the locked door, then we might have thought to check the windows. But we defined our problem as the door locking behind us, and never widened our field of vision to look for another solution.

With hyperkyphosis, the door we fixate on is the overly rounded upper back. It seems to be well and truly locked. And because rounding increases with age, our explanation for why it happens boils down to this: kyphosis is just part of the price you pay for not dying young.

Here’s an especially grim analysis from the Medical University of South Carolina:

“Between each vertebra, there is gelatin-like cartilage … With age, these discs harden and lose flexibility with the inevitable result of compressed total length of the spine and a forward tilt called kyphosis. These aging changes together are called senile kyphosis and are considered a normal part of aging.”

Missing the Clues

Given the circumstances, we focus our therapeutic and preventative energy on straightening the 12 thoracic vertebrae any way we can. You can buy an array of devices to improve your posture, from shoulder braces to gadgets worn between your shoulder blades that will buzz when you slouch. YouTube is awash with exercise courses to mobilize your thoracic, or strengthen your core, or release your shoulders.

Yoga, Pilates, and virtually every other movement discipline offer some form of intervention for the thoracic spine.

I gave the yoga approach a good solid try for almost 30 years.

In the end, I had mobility. I was able to arch my upper back over a wood brick like nobody’s business. But when I wasn’t bending it backward, my upper back still rounded. My progress toward my mother’s hump had slowed, but I was still on track to get there. I followed the program and put in the work. So why was I still rounding?

Did I really have to accept that age and genetics were against me? Or was it time to check for an open window somewhere nearby?

Hyperkyphosis and Your Pelvic Position

First, we need to ask if it’s possible if something is at work, apart from age, that hardens and stiffens our discs and rounds our backs. Why is it so difficult for us to stand up straight in the first place? Why is healthy posture such hard work? Why isn’t it easy and normal to have a long, strong spine as we age?

In fact, as soon as we step back from focusing on the thoracic spine, and instead look at the whole body in space, one obvious observation stands out:

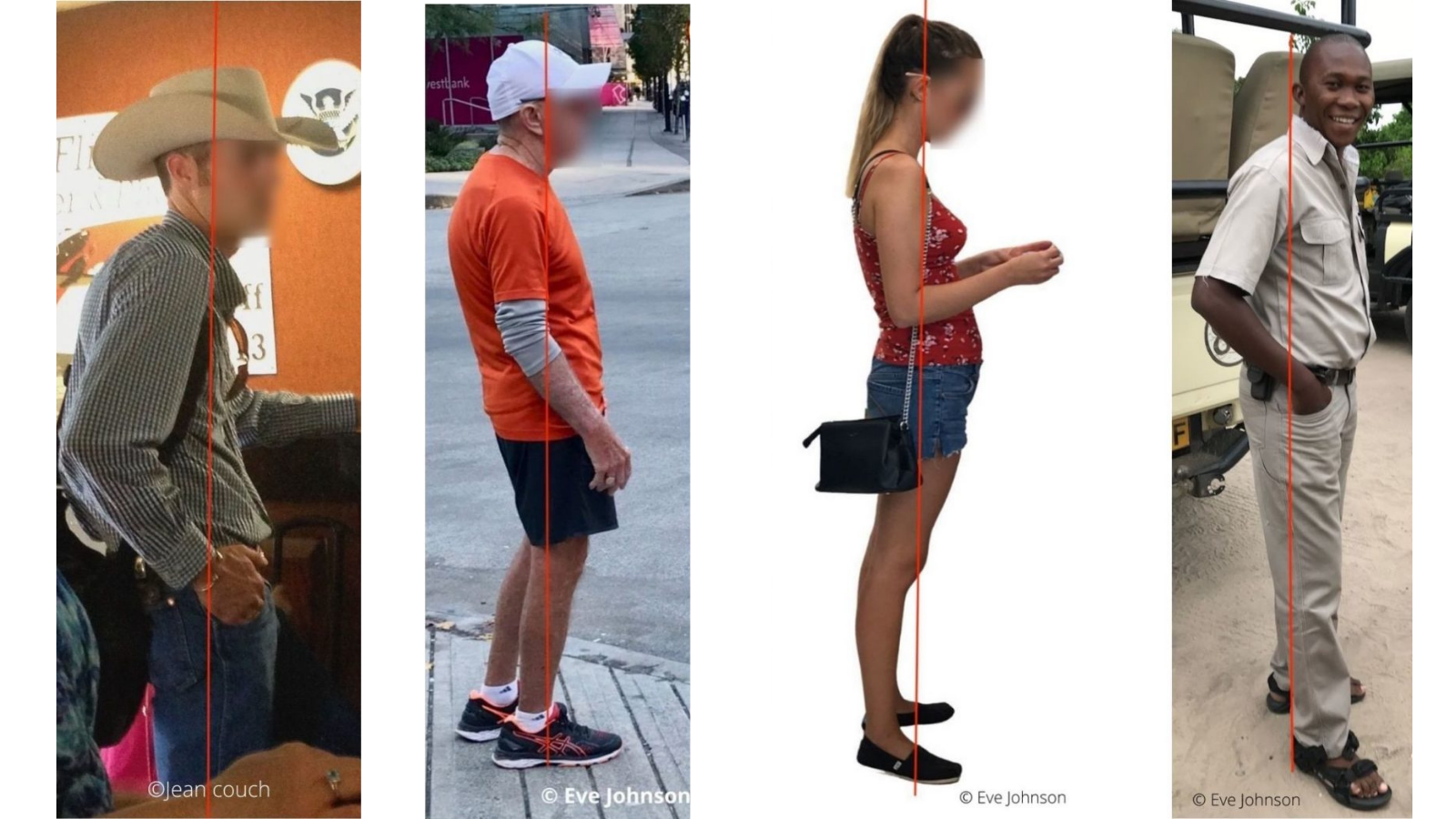

In these images of people standing, you can see that the three people on the left stand with their pelvis pushed forward and their buttocks tucked under. Some are more extreme than others, but the effect is the same: their upper backs round in compensation.

The man on the far right is in balance. The center of his pelvis lines up with the center of his ankle (check his back foot). His spine is long and straight.

Aligning with Gravity

For a structure to balance, a weight carried forward of the line of gravity needs to be counterbalanced by a weight carried behind the line of gravity. When we push our pelvis forward, the thoracic spine moves back. Then the head moves forward, even in the absence of a cell phone.

In this position, our weight no longer transfers easily through our bones. Instead, the muscles of the upper back and neck tense around the curved spine to hold it in place. Minute by minute, we shape ourselves into a rounded upper back and head-forward curve.

The same dynamic continues when we sit down. The tucked pelvis of standing translates into a tucked pelvis in sitting. We roll back and sit on our buttocks. That curves the lower back and shapes our spine into a giant C.

Look first at their lower backs: both the boy and the man sit far back on their buttocks. In this position the spine is forced to round back, creating a large thoracic curve. They could try to sit up straight and roll their shoulders back, but the laws of physics are against them.

When we curve, we compress the front of the intervertebral disc, and open the back too wide. Held in place over time, the discs get less circulation and get stiff and dry.

So yes, there is a mechanism at work that rounds our spine No need to call on aging to explain it. Physics will do just as well.

Hyperkyphosis: How to Restore an Upright Spine

To restore a long straight upper back, we do need to focus on our spines. But the area we should be concerned with is not the thoracic. The rounding there is a symptom of an imbalance elsewhere, not an independent phenomenon. If we can move our pelvis back into place, we can restore the health of the lumbar spine, the five large, weight-bearing vertebrae below the ribcage. When the lumbar is healthy, we can stop creating hyperkyphosis just by the way we sit and stand.

The next project, once we’re no longer doing ourselves harm, is to restore mobility, re-align our heads and shoulder girdles, and break the habit patterns that rounded our back in the first place. This all takes time, persistence, and a new understanding of living in harmony with the laws of gravity.

On the plus side, it works. And it does so because it solves the cause of the problem, rather than obsessing about a symptom.

Reprinted with permission from Eve Johnson's Spinefulness.ca

Images courtesy of Eve Johnson and Jean Couch

Eve Johnson taught Iyengar Yoga for 18 years before being introduced to Spinefulness in 2016. Convinced by the logic, clarity, and effectiveness of Spinefulness alignment, she took the teacher training course and was certified in July 2018. Eve teaches Spineful Yoga over Zoom and offers an online Spinefulness Foundations course. For course information, go to http://spinefulness.ca.

Featured Courses