View basket (0 items $0.00)

Error message

- Notice: unserialize(): Error at offset 5 of 154 bytes in variable_initialize() (line 1202 of /home/dh_6hcdc2/yogau.online/docroot/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- The file could not be created.

- The file could not be created.

Exhale: Breathing for Vagal Tone

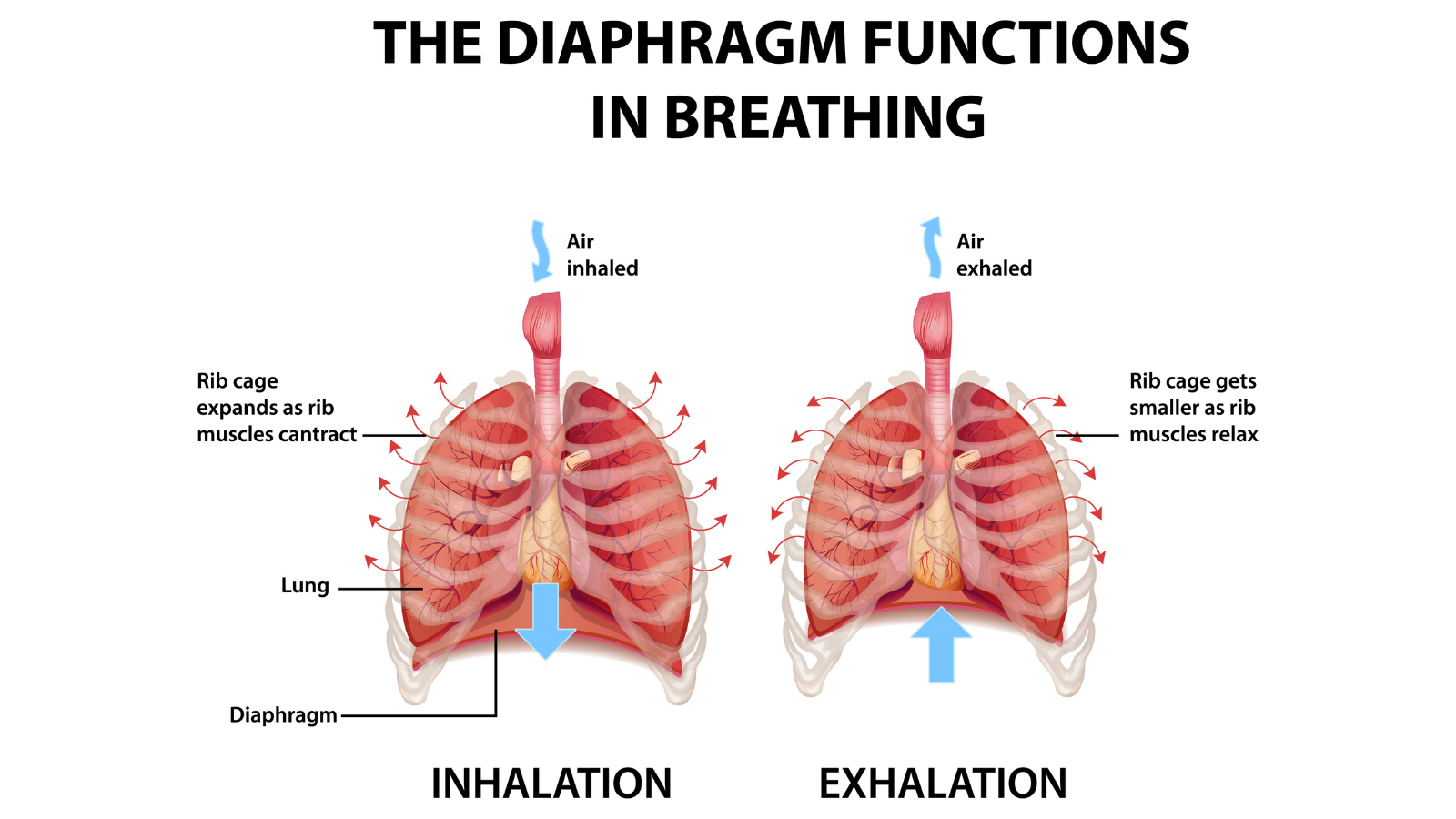

If you are a shallow breather, chances are you hold a lot of tension in your neck and shoulders. Chest breathing is short and located mainly in the chest and upper back. This means you are not benefitting from a full diaphragmatic and functional breath.

Chest and neck tension also relate to subtle or obvious anxiety and fear. These emotions can activate the vagus nerve to put us on high alert as we search for emotional or physical safety from real or perceived danger.

From the standpoint of the inner web of fascia, our connective tissue, there is no separation between the vagus nerve, the diaphragm, or the heart. What affects one will affect the others.

What Is the Vagus Nerve?

The vagus nerve is the longest and most complex of the 12 pairs of cranial nerves that emanate from the brain. The vagus nerve has two branches—abdominal and dorsal—that regulate abdominal functions and heart rate. Most of its information is sent from the body to the brain via afferent or ascending nerves.

The vagus nerve is the longest and most complex of the 12 pairs of cranial nerves that emanate from the brain. The vagus nerve has two branches—abdominal and dorsal—that regulate abdominal functions and heart rate. Most of its information is sent from the body to the brain via afferent or ascending nerves.

The vagus nerve is mainly responsible for regulating and balancing the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS) nervous systems. These two aspects of your autonomic nervous system are responsible for your emotional responses and expression. When we experience stress, anxiety, or fear, the vagus nerve will fire, producing a sympathetic fight-or-flight response. We feel this in various ways, including increased heart rate, rapid breathing, abdominal tension, digestive distress, and/or back pain.

The Little Brain of The Heart

In 1991 Dr. Andrew Armour of the UCLA Neurocardiology Research Center *1 discovered the heart is home to over 40,000 cognitive cells he called the “little brain of the heart,” or the intrinsic cardiac nervous system. What is really interesting is that the heart can make decisions independent of the brain and can communicate those decisions to the brain through the vagus nerve. Amazing, right? *2

Because of this connection and the fact that the vagus nerve is 80 to 90 percent sensory, your autonomic nervous system continually responds to subtle information from your inner and outer environment. This includes your cherished memories and beliefs, as well as any negative self-talk you revisit over and over.

So whether your vagus nerve is responding to past memories of stress, as in PTSD, or current anxieties and fears, it can become hypersensitive and reactive, altering your breath, heart rate, diaphragmatic tone, and emotional responses.

You stimulate your vagus nerve when you have a habit of chest breathing or focusing on negative thoughts. Over time this tends to lead to loss of tone and inability of the vagus to successfully regulate your sympathetic and parasympathetic responses. *3

Heart-Rate Variability Reflects Vagal Tone

According to Patrick McKeown, a leading international expert on breathing and sleep and author of The Oxygen Advantage, a healthy heart rate varies in intensity, speed, and rhythm to help us maintain the balance and ability to respond quickly (sympathetic nervous system) and recover with ease (parasympathetic nervous system) when faced with a challenging event. This is called heart rate variability (HRV) and is linked to both breath and emotion. “HRV is measurable and allows researchers to study stress as a physiological issue rather than a purely psychological or emotional issue,” writes McKeown. *4

He emphasizes that when the vagus nerve is stimulated over and over, as in chronic stress, the sympathetic nervous system goes into overdrive, which causes the heart rate to increase and remain high. In this heightened state, the heart is less flexible, and the variation between beats is smaller. This indicates that the system has lost some of its heart rate variability and vagal tone, both indicators of reduced health.

Chest Breathing vs. Diaphragmatic Breathing for Vagal Tone

Fortunately, improving and sustaining healthy heart rate variability and vagal tone levels is possible by shifting from chest to diaphragmatic or functional breathing.

Fortunately, improving and sustaining healthy heart rate variability and vagal tone levels is possible by shifting from chest to diaphragmatic or functional breathing.

Try this for yourself:

-

Using the image of a jellyfish swimming, focus your attention on the circle of the diaphragm to expand it evenly front, back, and sides on the inhalation.

-

Then circularly fold the upper and lower abdomen on the exhalation, like a jellyfish squeezing its long tentacles to propel itself through the water. *5

During inhalation, the sympathetic nervous system causes the heart rate to speed up slightly. During exhalation, the vagus nerve secretes acetylcholine. This triggers the parasympathetic nervous system to slow the heart rate and lower blood pressure. Because the out-breath is directly controlled by the vagus nerve, by increasing the length of your exhalation it is possible to stimulate the vagus nerve to activate at will the parasympathetic nervous system’s rest-and-digest response, according to McKeown.

How Long Should You Exhale?

While a fair amount of research is available indicating the optimal breath for increased heart-rate variability and vagal tone is an even 5.5 counts in and 5.5 counts out, it may not be appropriate in all situations. *6

In a situation where the vagus nerve may be hypersensitive, as in chronic stress or anxiety, slow, even breathing could actually evoke unresolved emotions and thus increase heart rate with an added loss of ease.

In those situations, the classic yoga breath technique to reduce emotional distress is to inhale four and exhale seven counts. In my personal experience of rapid heart rate and loss of vagal tone due to sleep apnea and anxiety, the longer exhalation is currently more beneficial to me than an even breath. It helps me to settle my heart while increasing my vagal tone through parasympathetic response. This, in turn, helps to settle my spirit in my body.

How long a person should exhale is variable according to the needs of the individual. When you practice jellyfish or functional breathing, you might observe that your exhalations naturally begin to lengthen. You may also experience a slight pause at the end of the exhalation.

Breathing for Vagal Tone: Focus on the Exhalation

Here’s how to practice for vagal tone:

-

Give your exhalation full attention, circularly hugging in from the upper to the lower abdomen until your pelvic floor contracts lightly and lifts, an action known in yoga as Root Lock (Mula Bandha).

-

Now also observe how tension in the upper chest and neck begins to melt.

-

Then relax your belly completely to begin your next circular inhalation. Let the breath fall into the lower abdomen and pelvis to allow the pelvic floor to receive the breath fully.

This type of breathing can be done anytime, anywhere to help you reduce anxiety and come fully present to the circumstances at hand and the unfolding possibilities. I recommend a regular practice of 3 to 5 minutes at a time.

This type of breathing can be done anytime, anywhere to help you reduce anxiety and come fully present to the circumstances at hand and the unfolding possibilities. I recommend a regular practice of 3 to 5 minutes at a time.

An important back-care course by Lillah Schwartz- Restore Your Fluid Spine: Yoga for Back Care & Healthy Aging

Reprinted with permission from Lillah Schwartz.

Lillah Schwartz, C-IAYT Certified Yoga Therapist, E-RYT 500, is an Asheville-based yoga teacher, teacher trainer, and author with more than 40 years of experience. She shares with students what she has learned from years of study with master yoga teachers and ongoing exploration about fascia, back pain relief, keys to healthy aging, and the physics of consciousness. Her teaching resources include her signature book, Healing Our Backs with Yoga: An Essential Guide to Back Pain Relief (2016), several courses designed for YogaUOnline, a YouTube Channel, a Vimeo class library, weekly Live Online classes, and private consultations. www.yogawithlillah.com

Lillah Schwartz, C-IAYT Certified Yoga Therapist, E-RYT 500, is an Asheville-based yoga teacher, teacher trainer, and author with more than 40 years of experience. She shares with students what she has learned from years of study with master yoga teachers and ongoing exploration about fascia, back pain relief, keys to healthy aging, and the physics of consciousness. Her teaching resources include her signature book, Healing Our Backs with Yoga: An Essential Guide to Back Pain Relief (2016), several courses designed for YogaUOnline, a YouTube Channel, a Vimeo class library, weekly Live Online classes, and private consultations. www.yogawithlillah.com

References:

1. Dr. Andrew Armour M.D. Ph.D. – Intrinsic cardiac neurons https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-8167.1991.tb01330.x

*1. The Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System: Dr. Armour on YouTube

*2. Heart Brain Communication / Heartmath Institute

*3. The Oxygen Advantage, Patrick McKeown, 2016

*4. Oxygen Advantage Vagal Nerve and HRV Research Online

*5. Breathing Practices to Support Mind/Body Health, article by Robin Rothenburg

*6. Heart Brain Communication / Heartmath Institute

Bonus Link- Breathing Techniques for Stress Relief https://www.webmd.com/balance/stress-management/stress-relief-breathing-techniques

Featured Courses